By Joshua Muravchik

https://www.nationalreview.com/magazine/2019/06/03/socialism-as-epic-tragedy/

May 16, 2019

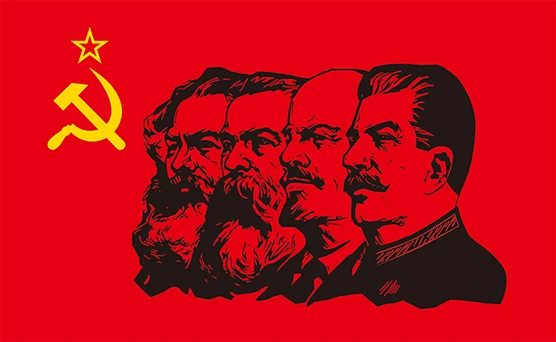

Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels,Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, and Joseph Stalin

The saga of socialism constitutes an epic tragedy. It was the most popular political idea ever invented, arguably the most popular idea of any kind about how life should be lived or society organized. Only the great religions can compare. Within 150 years from the time the term “socialism” was coined, some 60 percent of the world’s people were living under governments calling themselves socialist. Of course, not everyone who lived under such a regime shared its philosophy, but many millions did embrace socialism, join socialist parties, vote for socialist candidates, and even kill and die for socialism.

The powerful allure of socialism lay in its appeal to idealism. Every major religion affirmed the superior importance of the spiritual realm as compared with material things. Socialism spoke to this value system, promising a secular path to its fulfillment — and, even better, one that entailed little sacrifice. Socialists reasoned that if only property were owned in common, everything shared, and the fruits divided equally, people would no longer have cause to vie with one another. A new day of brotherhood would dawn. Freed from competition and invidious distinctions, individuals could enjoy a closeness they had never known before.

And there was more. No longer obsessed with the scramble for wealth, individuals could instead pursue self-fulfillment. I might hunt in the morning, fish in the afternoon, and write criticism in the evening, said Marx. Individuals could thus focus on developing their talents. Every person, said Trotsky, could become a Beethoven or a Goethe.

There would no longer be want. Not only would the sharing of goods ensure sufficiency for all, but also, instead of wasteful production for profit, economies could be focused on producing for need. Schools and libraries might be built instead of casinos or brothels, mass transit or family sedans instead of thrill or prestige cars, and so on.

The early socialists, starting in the 1820s, created model communities, hoping to demonstrate the superiority of the system they espoused. These all fell apart, usually quickly. But the fact that the system proved difficult to put in place did not negate the beauty of the idea, and few socialists plumbed the question of why, exactly, it was so difficult to create and sustain this system.

In any event, Marx and Engels soon appeared and rescued hopes, dismissing the early experiments as “utopian” and thus devoid of meaning. Instead, the duo claimed to have discovered laws of history revealing socialism to be mankind’s more or less inevitable destiny. The deus ex machina that would dig the grave of capitalism was the “proletariat,” a fancy word for the working class. Ruthless competition would compel capitalists to squeeze the compensation of employees until the workers, finding themselves constantly more miserable and exploited, rose up and overthrew the system, replacing it with socialism.

Oddly, this prophecy did not induce complacency. On the contrary, Marx and Engels became intensely involved in socialist organizations and parties. In their footsteps, socialists thereafter balanced the confidence of being on the right side of history with political activism intended to help history along. But new disappointments were in store.

In the 1890s, half a century after Marx and Engels set forth this vision, their intellectual heir, Eduard Bernstein, the one who had been chosen by Engels to produce volume four of the socialist bible, Capital, just as he himself had produced volumes two and three from the notes Marx had left, confessed to the observation that events were not bearing out the Marxian prophecy. The workers exhibited no interest in revolution for the apparent reason that they had been experiencing steady improvement in their material conditions rather than the forecasted deterioration. Economic historians now estimate that the standard of living in the advanced countries roughly doubled over those 50 years. Bernstein had access to no such data, but in contrast to Marx and Engels, he hailed from the working class and was intimately familiar with its vicissitudes, and thus was well equipped to assess changes in diet, wardrobe, and the like.

Bernstein drew the logical conclusion. He abandoned socialism. He determined to continue struggling to wrest better conditions for the workers, but he said, “The ‘final goal of socialism’ is nothing to me.” Others, however, were not ready to abandon the “final goal.” Although workers’ lives may have improved, their lot was still harsh. More important, the point of socialism was not only to ameliorate the plight of workers; the larger goal was to build a new society more harmonious and humane than any before.

In sum, socialism had reached a crossroads. If the workers were not going to create the revolution as predicted by the Marxian model, then a socialist had to choose. One could choose, as Bernstein did, to stick with the workers but give up on the revolution. Or one could choose to stick with the revolution but look to people other than the workers to bring it about. That was the choice of Lenin.

He shared Bernstein’s premise. In his terminology, history had shown that, left to their own devices, the workers would achieve only “trade-union consciousness,” not “revolutionary consciousness.” In other words, they sought higher wages, not bloody upheaval. But Bernstein’s conclusions enraged him. The majesty of socialism could not be forgone just because workers’ standards of living had risen. If the workers would not make the revolution, someone else had to.

Lenin hit upon the idea of creating a party of professional revolutionaries who would fill this role. They would not merely act in the name of the workers or for the benefit of the workers. They would collectively constitute the “vanguard of the proletariat” even though Lenin acknowledged that individually they would not be, or would not mostly be, proletarians.

This metaphysical leap may have been hard to follow, but it worked — at least insofar as Lenin’s band succeeded in seizing power and proclaiming the world’s first socialist state. Knowing that he commanded the allegiance only of his “vanguard,” an armed minority, Lenin then felt, with reason, that he had little means of ruling other than to prohibit opposition and cow the populace into obedience. He exhorted his followers to exert “merciless mass terror against kulaks, priests, and White Guards; persons of doubtful standing should be locked up in concentration camps.”

Lenin, to be sure, harbored an extraordinary thirst for power, but he was not merely out for power. He had a mission: socialism. In Russia, where the economy was predominantly agricultural, that meant collective farming. But the farmers, wanting nothing of the sort, resisted passively. Faced with economic disaster and civil war, he backed down on collectivization. But his successor, Stalin, renewed the struggle, engineering a famine, in which some 5 to 10 million starved to death, in order to secure the peasantry’s capitulation.

If Stalin was a tyrant of stupefying brutality — what previous despot had deliberately starved his own population? — he was matched or even outdone by such other Communist rulers as Mao and Pol Pot. Of this dynamic, Milovan Djilas, once a top leader of Yugoslav Communism, said: “How could they . . . act otherwise when they ha[d] been named by . . . history to establish the Kingdom of Heaven in this sinful world?” Had these men wished only to rule and enjoy the perquisites of unbridled power, they would have killed fewer. It was their devotion to an ideal that prompted them to slaughter millions of unresisting innocents.

Nor was this all. The idea propounded by Marxism of a redemptive future toward which history is trending but that can be helped along by mass violence proved open to permutation. Just as Lenin substituted the vanguard for the proletariat, Mao and Pol Pot added the wrinkle of substituting the peasants for the workers and then the vanguard for both. Mussolini, who was weaned on Marxism, spun another twist, replacing class with nation. He argued that downtrodden Italy belonged to the “proletariat” among nations while the wealthier states of northern Europe were the “bourgeoisie,” the enemy. Then Hitler replaced the nation with the so-called Aryan race and identified the Jews as the enemy class of his National Socialism. Thus, the ideal of a new brotherhood yielded one episode of mass murder upon another, altogether sketching as sanguinary a chapter as history has ever known.

No comments:

Post a Comment