By Mike Klingaman

https://www.baltimoresun.com/sports/nfl/bs-sp-colts-marchetti-obit-20190430-story.html

April 30, 2019

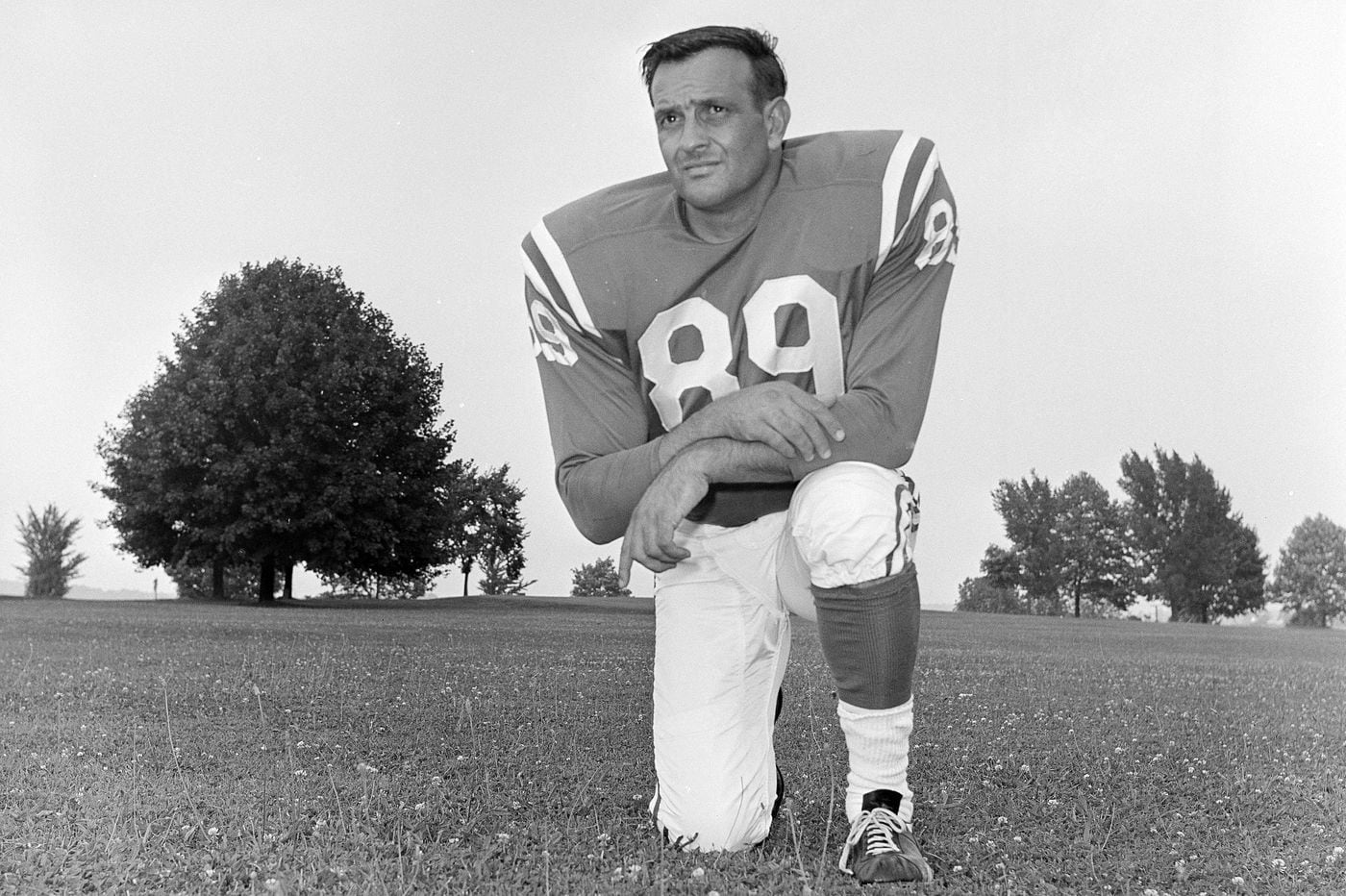

He was rugged, rangy and relentless in his pursuit of quarterbacks. For 13 years during their heyday, the Baltimore Colts were defined by a slab of a man known simply as Gino.

No Colts player epitomized the club — or the city — better than Gino Marchetti, the Hall of Fame defensive end who died Monday of pneumonia. Mr. Marchetti, 93, passed away at Paoli Hospital in Paoli, Pa.

“I kissed him and he knew me and smiled,” said Joan Marchetti, his wife of 41 years. “That was Gino’s way of saying goodbye.”

The son of an immigrant coal miner, Mr. Marchetti rose from lunch-pail environs to become captain of the two-time world champions (1958-59) and one of the most feared pass rushers in NFL history. He often played hurt; he always played hard. Colliding with the 6-foot-4, 245-pound Marchetti, Detroit quarterback Bobby Layne once said, was "like running into a tree trunk in the dark.

Swift and smart, Mr. Marchetti was the prototype of the modern defensive end, said Don Shula.

"He revolutionized the way you play that position in the NFL," said Mr. Shula, former Colts player and coach. "Prior to Gino, the attitude [of pass rushers] was to try to physically overpower the offensive tackle. Gino showed that with good instincts and a lightning quickness, he could get around his man without really engaging him.

"The offensive tackle's uniform never got very dirty, but the quarterback's sure did."

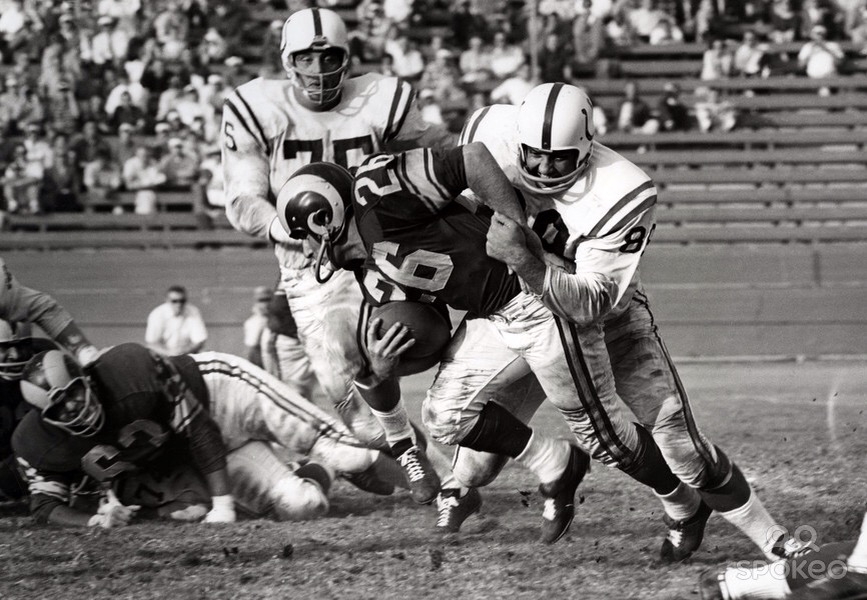

Those almost balletic moves — Mr. Marchetti could leapfrog over a man to make a tackle — and his ability to muscle linemen aside made No. 89 the bane of enemy backfields and a favorite of Baltimore fans.

"Gino romanticized defense," The Evening Sun's Bill Tanton wrote.

Dark-haired and swarthy, Mr. Marchetti won the city's heart with a string of gritty comebacks from injuries. Appendicitis in 1954. A dislocated shoulder in 1955. Neither sidelined him for more than a month.

In 1958, as he was making a saving tackle in the NFL championship game, Mr. Marchetti's ankle snapped. Lying in the Colts' dressing room, waiting to hear the outcome, he muttered, "If we win this game, it's worth getting a broken leg."

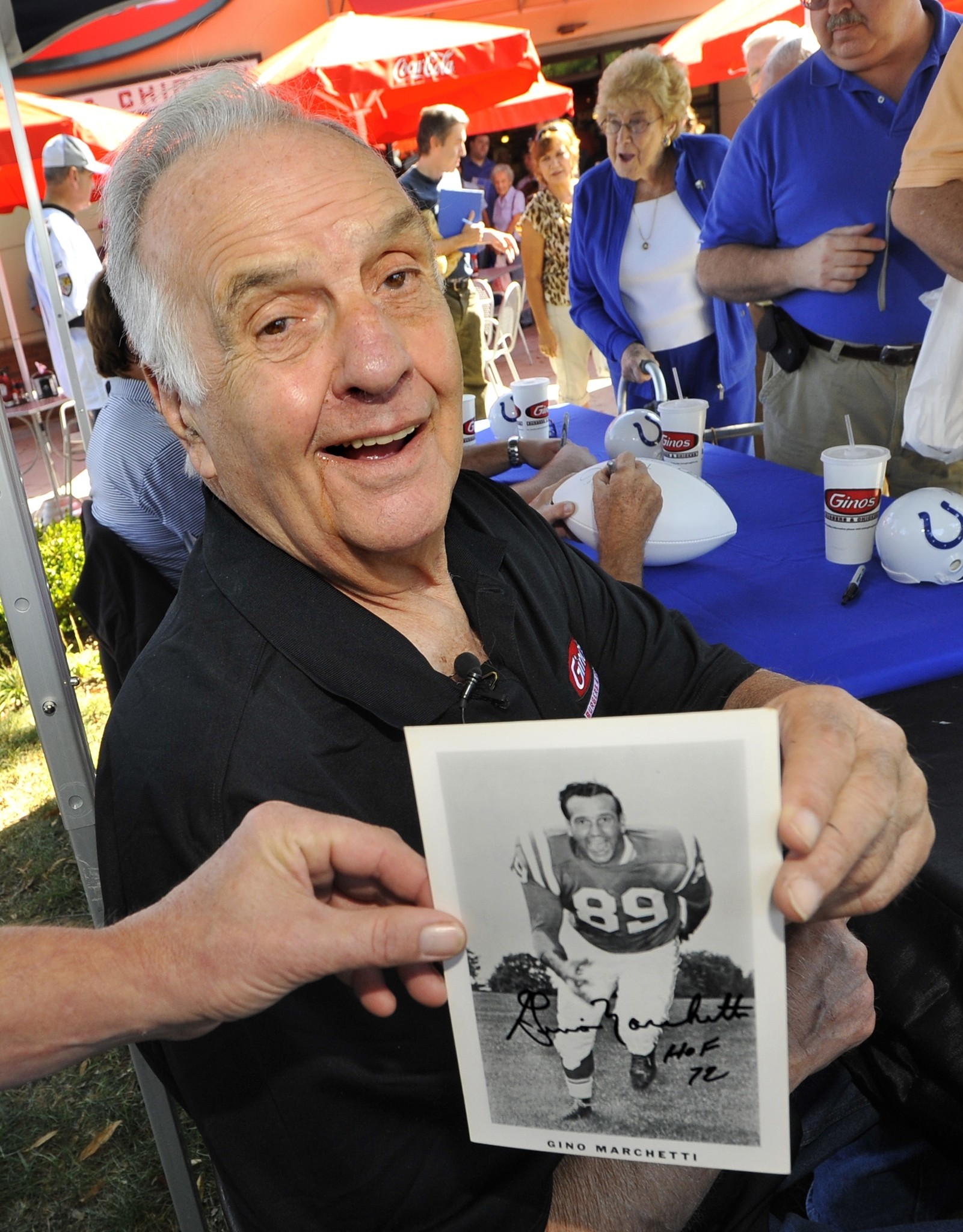

Four months later, egged on by the club's owner, Mr. Marchetti and two teammates opened a burger joint on North Point Road in Dundalk. Crowds flocked to the drive-in for the double-decker "Gino Giant" and a chance to meet the sandwich's namesake. By 1982, "Gino's" had mushroomed into a nationwide chain of 469 fast-food restaurants when it was sold to Marriott International for $48 million.

Though he played in the era before sacks were an official NFL statistic, Mr. Marchetti's legacy has never depended on numbers. In 1969, he was named the best defensive end of the NFL's first half-century. Three years later, in his first season of eligibility, Marchetti entered the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

In 1994, he was one of three defensive ends selected to the NFL 75th Anniversary All-Time Team, alongside David (Deacon) Jones and Reggie White.

On Tuesday, teammates remembered Mr. Marchetti as a giant on and off the field. "He was my man, a great human being," said Lenny Moore, 85, the Colts' Hall of Fame running back and receiver. An African-American player in the Jim Crow era, he remarked of his white teammate: "With all of the racism and stuff going on then, Gino was right there in our corner, and we never forgot that. This hits the heart."

Dan Sullivan, 79, an offensive guard who played with Mr. Marchetti for four years, recalled going one-on-one against him in practice. Time and again, Mr. Sullivan said, "Gino would put a quick move on me and I'd fall flat on my face. One quick step and he was past you. There wasn't a defensive end his equal."

Bob Vogel, an All-Pro offensive tackle and the Colts’ No. 1 draft pick in 1963, won’t forget the first time he lined up against Mr. Marchetti in training camp.

“Talk about a lamb being led to slaughter,” said Mr. Vogel, 77. “He went around me and through me. It was like he was saying, ‘I can put slick moves on you, but I can also run over your skinny butt.’

“But I also remember Gino sitting next to me on the plane after we got stomped in San Francisco that year. He said, ‘We will come back from this; don’t be discouraged.’ Here was the king of kings, talking to a kid who was wondering why the Colts drafted him. That was a precious moment for me.”

Born in Kayford, W.Va., Gino John Marchetti might have followed his father into the mines, had the family not moved west during the Great Depression. They settled in Antioch, Calif., where Mr. Marchetti grew up, the fourth of five children, chafing to follow his siblings into high school football.

"I remember sneaking into my oldest brother Lino's room and trying on his uniform," Mr. Marchetti told The Sun in a 2006 interview. "I was 9 at the time. The uniform didn't fit, but I sure enjoyed wearing it when Lino wasn't at home."

The summer before his freshman year, Mr. Marchetti worked in a laundry to earn money for football shoes. He got the shoes but failed to make the team at Antioch High. Undaunted, he rooted through the school's garbage, found an old uniform, dressed and begged to practice with the varsity. His wish was granted.

"I didn't become a starter until my senior year," he said. "Then we lost every game."

It was 1944. Mr. Marchetti left school, enlisted in the infantry and was sent to Europe toward the end of the World War II. His was the first U.S. battalion to link up with Soviet troops at the Elbe River in Germany in April 1945.

"I got a lot stronger in the army," he said. "Carrying a 42-pound machine gun all over Germany helped."

Returning home, he tended bar and played semi-pro football for two years. When another of Mr. Marchetti's brothers, Angelo, was recruited by Modesto Junior College, Gino tagged along on a whim. Homesick, Angelo dropped out. Gino stayed at Modesto and starred at tackle.

In 1948, an assistant coach at the University of San Francisco heard of his exploits and invited him for a tryout. Mr. Marchetti rode onto campus on his Harley, a long-haired motorcyclist dressed in a leather jacket "that was so cool I think it had 17 zippers," he said.

"I walked into Head Coach Joe Kuharich's office wearing motorcycle boots with metal heels that clanked,” Mr. Marchetti said. “When I left, Kuharich asked his assistant, ‘Where did you find that hillbilly?’ ”

"Don't worry," the aide said. "He can play."

A two-way tackle, Mr. Marchetti started all three years at USF, which went undefeated in 1951. The Dons might have played in the Orange Bowl had they not been an integrated squad. Bowl officials suggested the team leave its two black players at home.

"Forget it," said Mr. Marchetti, the captain.

He was the second-round draft choice of the New York Yanks in 1952, but the franchise moved to Dallas before Mr. Marchetti's rookie year. Despite his stellar play on defense, Dallas folded after one awful (1-11) season and became the Baltimore Colts.

The Colts moved Mr. Marchetti to offensive line — for one season. In 1954, new coach Weeb Ewbank returned him to defensive end, his favorite.

"There's too much structure on offense," Mr. Ewbank told Marchetti. "You need to play by the seat of your pants."

Mr. Marchetti's response?

"I could have kissed Weeb," he said.

He went on to be selected to 11 Pro Bowls, lead the Colts to back-to-back championships and wreak havoc on the rest of the league.

"[Mr. Marchetti] knocked down blockers like they were rag dolls," San Francisco lineman Leo Nomellini once said. "He had the look of death in his eyes on the field."

Sundays always found Marchetti nervously pacing the dressing room, five hours to kickoff.

"I probably walked 30 miles before the game," he said.

The thought of facing Mr. Marchetti gave adversaries the jitters as well.

"You'll never know the sleepless nights I had when Green Bay was getting ready to play Baltimore," said Forrest Gregg, the Packers' Hall of Fame offensive tackle.

Exploding off the line, Mr. Marchetti had the speed of a running back for the first five yards.

"He came off the ball like he was shot from a cannon," Ordell Braase, the Colts' other defensive end who died last month, had once said. "I have a photo on my wall of me sacking Detroit's Earl Morrall. That's probably the only time I got to the quarterback before Gino did."

Mr. Marchetti's secret?

"At the line of scrimmage, I never watched the ball. I'd watch the three guys opposite me," he said. "If the guard left a split second before the tackle did, I was off. You could tell the play from the way they leaned, or the way they put their knuckles down.”

Defensively, the Colts paired Mr. Marchetti with Art Donovan, a burly left tackle. The two proved a perfect match. Mr. Marchetti was tall and lean; Mr. Donovan wasn't. Mr. Marchetti rarely spoke; Mr. Donovan seldom fell silent. But on the field, few teams could handle the tandem of Gino The Giant and his sidekick, Fatso.

"Sometimes my speed would get me in trouble, and Artie's quick reactions would save me," Mr. Marchetti said. "And sometimes when he couldn't get outside quick enough, I'd be there.

"I felt real comfortable with Artie next to me."

Once, they wound up sidelined at the same time in Union Memorial Hospital. Nurses found the two in their room, mixing highballs in an ice pitcher and using a thermometer as a stirrer.

Ironically, Mr. Marchetti's broken ankle, suffered in the fourth quarter of the Colts' sudden-death victory over the New York Giants in 1958, might have helped Baltimore win the championship. On a third-down play, he tackled Giants' runner Frank Gifford near the first-down marker, then was buried in the pile-up. Mr. Marchetti's screams distracted officials who, in the aftermath, might or might not have misplaced the football.

Six stretcher bearers hauled Mr. Marchetti off the field. When play resumed, the Giants were forced to punt.

Afterward, in the visitors' jubilant dressing room, a News-American reporter described the injured lineman: "Here he stretched on a training table deep in the stadium, six-feet-four of battered bliss — a fractured ankle on one end and a face split with a marvelously happy grin on the other, the game ball clutched to his chest."

Mr. Marchetti was "the greatest player I ever played with," the late Jim Parker once said.

"For 11 years, I thought the Colts were going to trade me and I was afraid I'd have to play against Gino — so I watched him real close," said Mr. Parker, a Hall of Fame offensive tackle. "I never saw anybody beat him, really."

Mr. Marchetti's deeds weren't limited to the playing field. In 1962, after a 7-7 season, the Colts fired Mr. Ewbank. On Mr. Marchetti's advice they hired Mr. Shula, then 33 and the youngest head coach in NFL history. Mr. Shula coached Baltimore to seven consecutive winning seasons en route to a place in the Hall of Fame.

Mr. Marchetti played his last game in 1966, at age 40. He retired on three separate occasions; the first two times, the Colts brought him back. He quit in 1963, but returned a year later to lead the team to the title game won by Cleveland, 27-0. Less than a minute remained when Browns quarterback Frank Ryan, wanting more points, called a timeout. Riled, Mr. Marchetti stormed across the line of scrimmage.

"As Gino walked toward Ryan, Cleveland's whole offensive line parted like the Red Sea," Colts runner Tom Matte recalled. "Gino pointed his finger at Ryan and said, ‘I'll get you for this.’ ”

Soon after, in the Pro Bowl, Mr. Marchetti collared the Browns quarterback, who suffered a separated shoulder on the play.

"It was a clean hit," Mr. Marchetti said. "But [Browns owner] Art Modell got on me about that in the locker room afterward."

Mr. Marchetti said Mr. Modell, who would eventually own the Ravens, never forgave him.

"I think that's why [Mr. Modell] never invited me to any Ravens functions," the lineman said.

Mr. Marchetti had a soft side, too. As team captain, he took part in the pregame coin toss. There, with all to see, he would tap his helmet with his right hand.

"That was a signal to my mother," he said. "It meant, ‘Hello, Mom. I love you.’ ”

Gino Marchetti signs autographs at the Gino's restaurant in Glen Burning (Baltimore Sun)

Gino Marchetti signs autographs at the Gino's restaurant in Glen Burning (Baltimore Sun)

Of all his accolades, Mr. Marchetti said his overall reputation as a clean player meant the most.

"I never got hit with a 15-yard penalty," he said. "No late hits. No clipping. No hitting out of bounds. I didn't make stupid mistakes or put the team in trouble."

Mr. Marchetti stayed active in later years. A heart attack in 1981 led him to shed 85 pounds he had gained since retirement. He enjoyed fishing in the Atlantic on his 40-foot boat in which he chased marlin off — where else? — the Baltimore Canyon.

Bowling was a passion. At age 79, he rolled a 299 in a seniors tournament, one pin shy of a perfect game.

In retrospect, he never thought of himself as a giant.

"I was just a little guy from Antioch who never had any idea of leaving," he told The Sun in 2006. "I figured I would go to high school, work in the mill, retire and go fishing in the Sacramento River. That was my plan. That's what you did."

Instead, he earned two World Championship rings, became a multimillionaire and hobnobbed with presidents and celebrities.

A favorite photograph hangs on the "Hall of Fame Wall" in his home in West Chester. It's a picture of the late Clark Gable surrounded by five Colts players who met the actor in 1960 at the airport in Los Angeles. Mr. Marchetti ticked off their names: Johnny Unitas, Alan Ameche, Bill Pellington, Carl Taseff and Mr. Marchetti.

Not bad for a little guy from Antioch.

On Tuesday, the Ravens acknowledged Mr. Marchetti’s passing in a statement, calling him “a giant of a man with a giant heart who helped many in need … we appreciate the kindness and respect Gino showed the Ravens over the last 23 years.”

Besides his wife, the former Joan Plecenik, Mr. Marchetti is survived by daughters Gina Burgess of Downingtown, Pa., and Michelle Kapp of Drexel Hill, Pa.; sons John Marchetti of Exton, Pa., and Eric Marchetti of West Chester, Pa.; stepdaughter Donna Lloyd of Mountain Top, Pa.; 16 grandchildren and 14 great-grandchildren.

Funeral services are incomplete but being handled by Alleva Funeral Home in Paoli.

No comments:

Post a Comment