By Bruce Jenkins

https://www.sfchronicle.com/giants/jenkins/article/Willie-McCovey-s-presence-was-one-of-a-kind-13353073.php#photo-16428390?utm_campaign=facebook-premium&utm_source=CMS%20Sharing%20Button&utm_medium=social

October 31, 2018

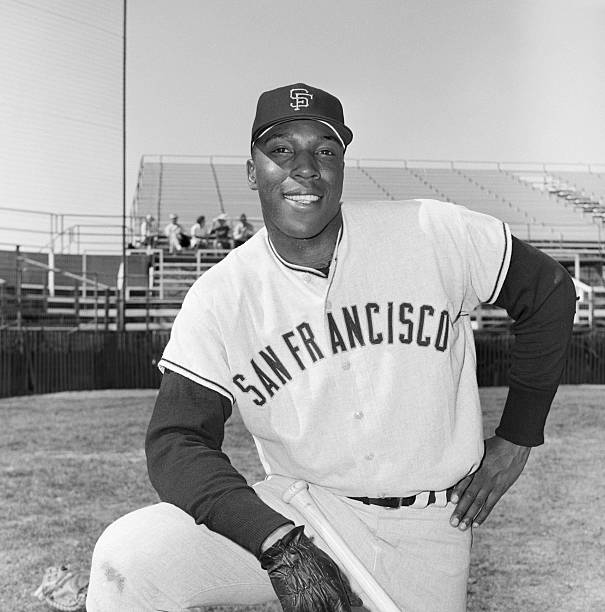

McCovey in 1964 (Getty Images)

A certain arrogance accompanied many of baseball’s most feared hitters over the years, the likes of Babe Ruth, Reggie Jackson and Barry Bonds inviting controversy with a roguish persona. Willie McCovey was the gentleman superstar, often described as a man without enemies.

McCovey, who died at the age of 80 on Wednesday afternoon, was among the classiest athletes ever to grace the Bay Area. Humble and soft-spoken, always clearly grateful for the life he was able to live, he stepped to the plate and cast a giant shadow over the proceedings — particularly the opposing dugout. In the wake of his titanic, tape-measure shots, a number of pitchers figured the most clever strategy was to just deliver four balls and let him walk.

Sparky Anderson, who managed the great Cincinnati teams of the 1970s, once said: “There’s no comparison between McCovey and anybody else in the league.” Such was the man’s presence, and nobody realized that more than the Giants. McCovey was once considered so valuable to the organization that the team was willing to trade future Hall of Famer Orlando Cepeda to solve a roster conundrum.

Seasoned fans won’t forget McCovey’s debut in the big leagues. Summoned from the minors on July 30, 1959, he was placed third in the batting order — between Willie Mays and Cepeda — for a game against the Phillies at Seals Stadium. Robin Roberts, one of the great pitchers of that time, was on the mound but McCovey was undaunted, going 4-for-4 with two triples as the Giants prevailed 7-2.

As formidable as he looked, it didn’t figure that McCovey would stick with the big club. The Giants had Cepeda, coming off a Rookie of the Year ’58 season, firmly stationed at first base. But returning to the minors would not be an option. McCovey hit .467 over his first seven games, had a 22-game hitting streak, and finished his two-month trial batting .354 with 13 home runs and 38 RBIs.

Just as certain batting stances stay in the memory through time — think Willie Stargell or Joe Morgan among the great left-handed hitters — McCovey’s was unmistakable. At 6-foot-4 and 200 pounds, he had a slow, languid practice swing that turned to lightning when the pitch arrived. Opposite-field hitting wasn’t his thing; he crafted a lifetime of memories with howling, dead-pull rockets, so many of them destined to cut through the San Francisco chill and over the fence by miles.

Imagine the conundrum for manager Bill Rigney and his successor, Alvin Dark. They experimented with Cepeda at third, while giving both McCovey and Cepeda a shot in the outfield, and as much as it hurt the club defensively, few teams in history could approach the potency of those two men in the same lineup with Mays. The three of them tormented National League pitching until 1966, when Cepeda was traded to the St. Louis Cardinals.

Not only did the Giants lose their most beloved player among the fan base, the Cepeda deal (for pitcher Ray Sadecki) goes down with the worst deals in franchise history. But it cleared the way for McCovey, who had battled knee problems from the beginning and was now set to play first base for the remainder of his career.

Gracious, what havoc he wreaked. In 1968, the so-called “year of the pitcher,” offensive numbers were so paltry throughout the majors, the pitcher’s mound was lowered for the following season. McCovey didn’t seem to get the message, leading the National League with 36 homers and 105 RBIs and finishing third in the MVP voting. The following year he won the award, posting his best-ever season with a .320 average, 45 homers and 126 RBIs.

That was right about the time pitchers figured out that there was no feasible way to get McCovey out. From 1969 through ’73, he led the league in intentional walks four times.

Among those who loved to challenge McCovey, the Dodgers’ Don Drysdale stood out. A tall, ill-tempered side-armer who loved to send hitters (including Mays) sprawling into the dirt with brushback pitches, Drysdale had no answer for McCovey. He said McCovey was the toughest hitter he ever faced, as if L.A. fans needed any reminders. From 1959 through ’62, he hit .543 with seven homers against Drysdale.

Giants lore is never complete without a most regrettable episode in the 1962 World Series. The Giants had finally made it, after many close-call seasons, and it came down to the climactic Game 7 against the Yankees at Candlestick Park. With two out, runners at second and third and the Yankees leading 1-0, many felt that manager Ralph Houk would walk McCovey and take his chances with Cepeda in a righty-righty matchup against pitcher Ralph Terry. Houk chose to pitch to McCovey, who hit a searing line drive directly into the glove of second baseman Bobby Richardson to end the Series.

McCovey could not have hit the ball any harder. Nor could the San Francisco fans have been any more heartbroken.

In recent years, McCovey served as a warm-hearted ambassador for the club, even as health issues confined him to a wheelchair. He always was on hand to present the award given annually in his name, signifying the Giant who best exemplified McCovey’s indomitable spirit. As difficult as it was for him to get around, he was a regular presence around the ballpark, joyfully reminiscing with old friends Mays, Cepeda and Mike Murphy, the venerable clubhouse manager.

Lucky were those who got to spend a little time around the aging McCovey. Even luckier were those who saw him play, that large, looming presence in the batter’s box, ready to unleash that mighty swing. Long live his memory.

Bruce Jenkins is a San Francisco Chronicle columnist. Email: bjenkins@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @Bruce_Jenkins1

No comments:

Post a Comment