By Jacqueline Cutler

https://www.nydailynews.com/features/ny-fea-babe-ruth-book-20181014-story.html

October 14, 2018

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/58302623/515616944.jpg.0.jpg)

He made things bigger just by being part of them.

Baseball, the Yankees, even New York – everything grew in his presence. George Herman Ruth Jr. – the Babe, the Bambino, the Sultan of Swat – connected with all of them as easily as his bat connected with the ball.

And sent them all soaring.

But, as Jane Leavy's "The Big Fella" explains, if Ruth's adult life was large and joyous, his childhood was small and mean. Born in Baltimore in 1895, he saw six of his seven siblings die in childhood. His father beat him. His mother drank.

George Jr. rebelled, playing pranks and stealing sips of beer at his dad's saloon. So the old man sent him to St. Mary's Industrial School for Boys, home for orphans and the "incorrigible or vicious." Little George was seven.

It turned out to be an unexpected blessing.

Run by the Xaverian Brothers, St. Mary's was far from comfortable. The boys got gruel for breakfast, soup for lunch and dinner. Meat was a once-a-week treat – hot dogs on Sunday. "I was always hungry," Ruth remembered later.

But there was baseball.

The school's Brother Matthias was a passionate fan, and fielded teams so good the Baltimore Orioles sometimes sent over scouts. In 1914, the team's owner, Jack Dunn, even came by to check out one young player. Still, he needed more than a slugger.

"Can he pitch?" Dunn asked.

"He can do anything," Brother Matthias said.

Dunn signed the 19-year-old Ruth for the 1914 season, for $600. Because Ruth was underage, and a ward of St. Mary's until he turned 21, Dunn also had to agree to become his legal guardian.

And that's how Ruth entered the major leagues. "Jack Dunn's Baby," as his new teammates cracked. The Babe.

Things moved quickly after that. The Orioles sold Ruth to the Boston Red Sox. He married a teenage waitress who had served him breakfast. And he pinch-hit in the 1915 World Series against the Phillies, which the Sox won, four games to one.

Ruth used his share of the Series bonus, $3,780.25, to buy his father a new bar. The Babe was simply unable to hold a grudge or do anything halfway.

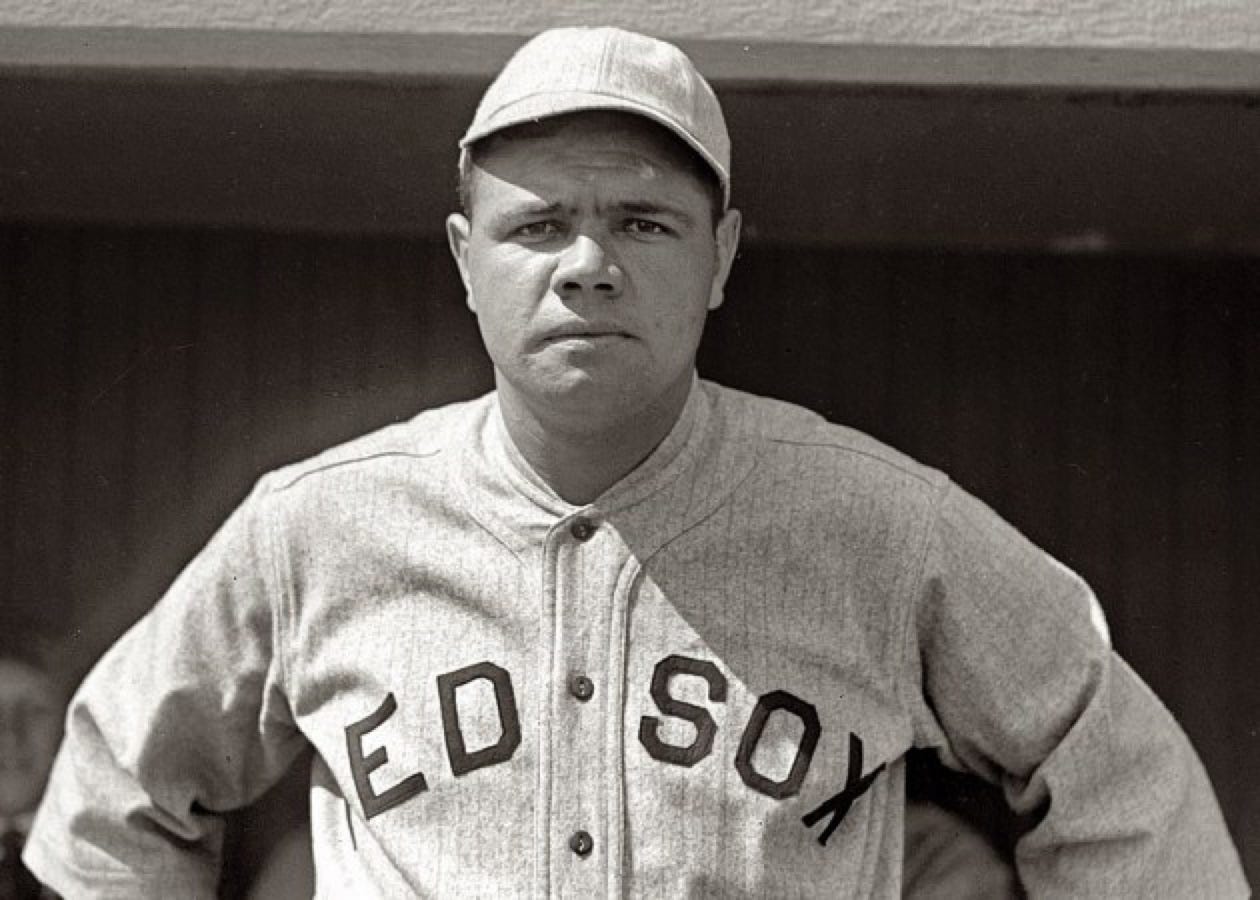

Babe Ruth, 1918 (Library of Congress)

By 1920, he was with the Yankees, hitting home runs and making $20,000 a year. Within ten years, he was making four times that. He wore silk shirts once, and threw them away. He had 18-egg omelets for breakfast, and four steaks for dinner. Beer came in by the barrel.

His hunger for women was just as huge. Ruth strolled around Manhattan with a chorus girl on each beefy arm, and flirted with flappers on the road. After sex, he'd light up a big cigar. In the morning, the hotel ashtray would always be full.

Childishly trusting, cheerfully irresponsible, the Babe in some ways, was a patsy, ripe for conmen. Luckily for him, he met Christy Walsh.

If Ruth were a unique figure in sports, Walsh remains nearly as rare – a cautious and devoted manager. Beginning as Ruth's press agent in 1921, he quickly expanded his duties. He put the player's earnings in safe investments. He arranged movie roles, merchandizing deals, personal appearances.

By 1927, Ruth was making more money off the field than on it.

Babe Ruth was now a business, and Walsh protected it fiercely. The only nagging annoyance was the popular Baby Ruth candy bars. Although Walsh sued for a share of the profits, the manufacturer successfully argued he named the confection after the long-dead daughter of former President Grover Cleveland.

Yeah, right.

But if it were still difficult to trademark the man, you could control the image. Walsh set up his own national feature syndicate, supplying papers with photos and articles. No one seemed to mind that much of it was posed or faked, including a column Ruth supposedly wrote, but probably never even read.

Controlling the Babe himself was more difficult. Prohibition didn't stop his drinking any more than marriage had stopped his dating. Pictures of one mistress even made the front page of the Daily News. Later, a paternity case – eventually dismissed – would loom.

Some rumors were uglier.

Opposing players sometimes yelled racial slurs at Ruth, who tanned easily. People called him ugly things since St. Mary's, and he was offended. Ruth was friendly with Negro League players and, when he visited hospitals, pointedly visited black ones as well and posed for publicity photos no white paper would run.

Some rumors may have been true. In 1921, an infant daughter suddenly appeared, although Ruth and his wife were vague about the details. Later, after the couple separated, Helen Ruth claimed the child was from one of her husband's affairs. But the couple stayed married until 1929, when Helen died in a house fire.

The Babe quickly remarried, and his new bride put him on an allowance and a diet. Some people are eternal optimists.

But nothing, of course, was likely to restrain the Babe or diminish the affection of his fans.

His popularity drove up Yankees revenues by roughly 20%; their new stadium really was "The House That Ruth Built." Post-season he toured the country with teammate Lou Gehrig, playing exhibition games that were often interrupted when souvenir hunters ran onto the field to grab balls still in play.

By the early '30s, though, Ruth was slowing down. He was no longer limber enough to field well, and his batting average – which had peaked, in 1923, at an amazing .393 – had slipped to .288 by 1934. It was his last year in pinstripes. He hit a sad .181 the next season with the Boston Braves, and announced his retirement from playing.

But not from baseball, or so he hoped. It was the only job he had ever had, and he was still only 40. Maybe someone needed a manager.

But his reputation preceded him, and the image that Walsh had protected, and had served Ruth so well as a player, the big, overgrown kid, left owners unimpressed. The guy listened to nobody. How would he ever get players to listen to him?

The game had moved on.

Other, private disappointments followed. For years, Ruth had been friends with Gehrig, gently teasing the younger man about his shyness and intense devotion to his mother.

But Mama Gehrig didn't approve of the new Mrs. Ruth, and when Babe told Lou his mother should mind her own business, the loyal son stalked off. It was only years later -- on July 4, 1939, when an ailing Gehrig gave his "luckiest man" speech at Yankee Stadium -- that the two reconciled with a hug at home plate.

Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig in the dugout before Game 2 of the 1939 World Series. (AP)

Within a few years, Ruth was ill too, although he still greeted fans and raised money for charities, including St. Mary's. By the time his authorized biopic, 1948's "The Babe Ruth Story" debuted, he was riddled with cancer. Too full of morphine to follow the story, he left the premiere after 20 minutes.

He died the next month. He was 53.

But the Babe is immortal, as long as somewhere some kid is throwing a ball, slamming a triple, making a catch. Or sliding quickly, deliriously, into the safest home there is.

No comments:

Post a Comment