https://www.nationalreview.com/2018/11/book-review-unbeaten-rocky-marciano-biography/

November 3, 2018

In 1976, in front of a fireplace at his rustic training camp in Deer Lake, Pa., Muhammad Ali sat with Howard Cosell for a Wide World of Sports special on great heavyweight champions. As black-and-white footage ran of his illustrious predecessors, Ali was mostly dismissive: Jack Dempsey had no science; Joe Louis was too slow afoot; fighters from the turn of the century were too primitive. Then Cosell got to Rocky Marciano.

“Marciano!” Ali exclaimed. “Ooh, he hit hard! . . . I did a computer fight with him, when he was an old man just pretending, and my arms were sore just from joking with him.” Released in movie theaters in early 1970, the Ali–Marciano “fight” had been filmed in summer 1969, not long before Marciano died in a plane crash. The idea was that Ali, then 27 and exiled from boxing due to his refusal to be inducted into the Army, and the retired Marciano, 45, would act out scenarios for a match as devised by an NCR-315 computer. The choreography was staged, but inevitably some real punches landed, and each man emerged from the experience with deepened respect for the other.

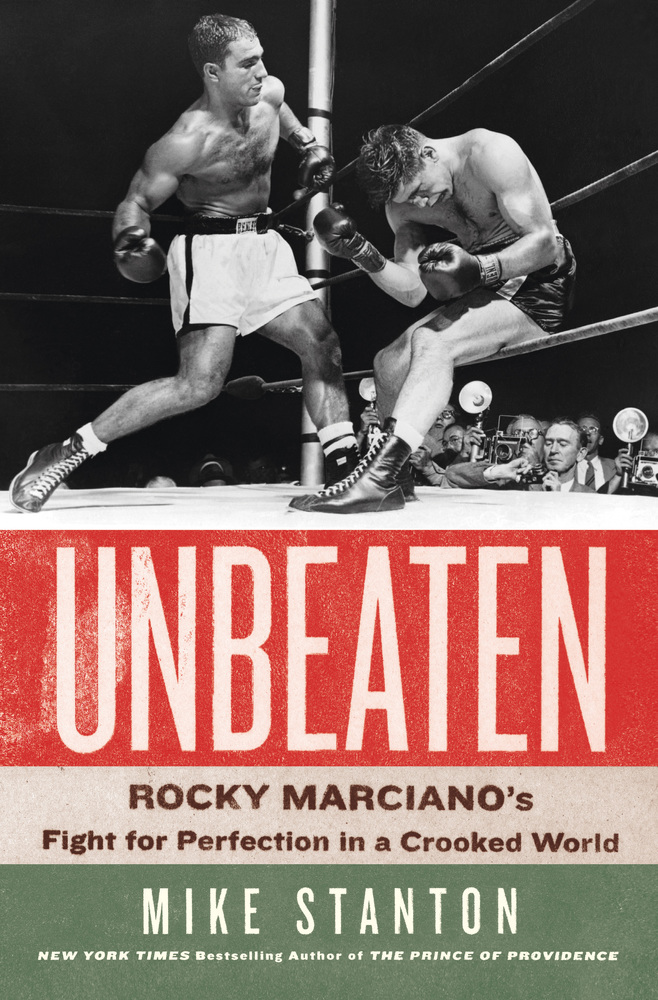

In his new biography, Unbeaten: Rocky Marciano’s Fight for Perfection in a Crooked World (Henry Holt, 400 pp., $32), Mike Stanton helps readers understand why even so proud a man as Muhammad Ali came to view Rocky Marciano, the pride of Brockton, Mass., as something like a force of nature. Stanton, author of the best-selling The Prince of Providence: The Rise and Fall of Buddy Cianci, is well positioned, geographically and professionally, to write the definitive Marciano biography, and that’s what Unbeaten appears to be. Stanton’s treatment of his subject is what you might expect from a longtime newspaperman who shared a Pulitzer Prize for investigative reporting at the Providence Journal: He runs down every source, providing rich detail — and fresh discoveries — about Marciano’s career.

The general outlines of that career are well known: Born in Brockton in 1923, Rocco Marchegiano dreamed of major league baseball stardom but lacked the skills, and, after a stint in the Army during World War II, resolved on boxing at the late age of 23. It was a last-ditch attempt to avoid the fate of his father, Pierino, who toiled in the city’s famous shoe factories. Linking up with uber-connected boxing manager Al Weill and resident-genius trainer Charley Goldman, Marciano had the right team to get him to the top, but he never would have made it there without the ferocious dedication that became his hallmark. Cursed with the shortest arms of any heavyweight, clumsy and unpolished, Marciano looked like the roughest of diamonds when Goldman got hold of him. “You’ve got so much to learn it ain’t funny,” the trainer warned.

But Marciano was single-mindedly determined to succeed. “I’ve been in this boxing business fifty years, and I’ve never seen anyone like you yet,” Goldman told the fighter after he became champion. “Work. Work. Work. Train. Train. Train. Sometimes I suspect you’re not even human.” Marciano’s work ethic and what Stanton calls his “indomitable will to win” were the key elements of his rise, along with a final ingredient, the only one supplied by nature: a right-hand punch that put even superior boxers to sleep. Marciano’s men called it the Suzy Q, and it delivered one of the sport’s central moments, in September 1952, when challenger Marciano planted the right on the chin of heavyweight champion Jersey Joe Walcott in the 13th round, knocking him out cold and winning the title. He reigned for a comparatively brief three and a half years, defending his crown six times before retiring in April 1956 with a perfect 49–0 record, still the only undefeated heavyweight champion. His fighting style, which depended on extraordinary physical conditioning, was often derided as crude, but it always got the job done. One opponent likened it to battling against an airplane propeller.

Stanton’s descriptions of Marciano’s signature battles against Walcott, Joe Louis, Ezzard Charles, and Archie Moore are engrossing and gritty, uncluttered with attempted literary flights of fancy. Though the author’s shoe-leather approach at times bogs down the pace, his doggedness mostly serves the story well, and it also makes some news: We learn that Marciano did not serve uneventfully in the Army during World War II, as long believed, but instead spent nearly two years in the brig, the result of a court-martial conviction for a drunken misadventure with a buddy, in which they were charged with the assault and robbery of two Englishmen. (Marciano secured an honorable discharge by rejoining the Army after serving his sentence.) A smaller surprise concerns Marciano’s end-of-life musings about the abolition of boxing, a prospect that he seemed to welcome. “As people get more civilized,” the ex-champ said, “they’re going to ban boxing. . . . A hundred years from now we’ll be like the gladiators, something out of history.” He worried that his grandchildren, in looking back over his life and career, might see him as “a brutal ruffian.”

These speculations sound surprising coming from such a rough-and-tumble fighter, but Unbeaten shows that Marciano was much more complicated than most people knew. His reputation as gracious sportsman and hard-working, clean-living family man made him an emblem of 1950s popular culture — “a poster boy for the Greatest Generation and a symbol of American masculinity,” as Stanton puts it — just as heavyweight champions before and after him would resonate with their own eras. But the spotless image obscured darker impulses, including fraternizing with mobsters, especially in retirement, and, also in retirement, indulging an insatiable appetite for women. His lifelong fear of going broke and distrust of non-cash money metastasized into a mania for squirreling away greenbacks in curtain rods and light fixtures around the United States. When he died on August 31, 1969, he hadn’t told any of his family where the money was, and they never found a dollar. Stanton’s depiction of Marciano’s retirement years is consistent with what earlier writers, such as Russell Sullivan and the late William Nack, uncovered, but his treatment is deepened by the context he provides on the younger Marciano — the one who spent time in an English stockade before rising to the heights of American sports. These early- and late-life bookends frame a boxing career that now looks like the orderly middle of a life otherwise dominated by restlessness.

That Stanton would find something new to say about Marciano is impressive considering that two fine biographies of the fighter already exist. Everett Skehan’s 1977 Rocky Marciano: Biography of a First Son provides deep local color, with firsthand testimonies from multiple Brockton insiders, while Sullivan’s Rocky Marciano: The Rock of His Times combines scrupulous biography with insightful social commentary. Published in 2002, Sullivan’s book looked to be the last word on the Rock, until Stanton came along.

Writing about Marciano in Sports Illustrated in September 1955, Budd Schulberg asked: “Are we too close to his shortcomings to recognize his incomparable virtues?” The question lingers, because, even with his perfect record, Marciano remains somewhat underappreciated. Whatever the Rock lacks in public memory, though, he now has, in Unbeaten, a Suzy Q of a biography.

No comments:

Post a Comment