“The Death of Stalin” Dares to Make Evil Funny

By Anthony Lane

March 19, 2018 Issue

There is a scary moment, in “A Man for All Seasons” (1966), when Henry VIII (Robert Shaw) jumps ashore from a stately barge. His feet sink deep into the mud, up to the royal ankles. We get a closeup of the King as he looks around, jutting his ginger beard and seeking someone to blame for this indignity. His glare is as hot as a branding iron. Every lackey quails, expecting to be whipped, or worse. Then Henry laughs. The threat has passed, but, for an instant, we glimpsed both his temper and his power, and saw that they amount to the same thing. Now imagine a whole empire run along such lines. Imagine a movie where the moment never stops.

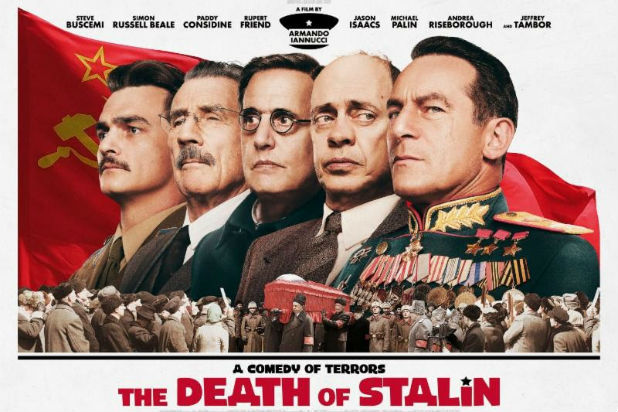

And so to “The Death of Stalin,” a startling new film from Armando Iannucci. The title does not lie. Less than twenty minutes into the movie, Joseph Stalin (Adrian McLoughlin) is found lying on a rug in his dacha, outside Moscow. It is March, 1953, and breakfast is ready, but the great leader has been felled by a stroke. Steeped in urine, he is soon surrounded by a small horde of henchmen from the Central Committee. First to arrive is Beria (Simon Russell Beale), Stalin’s fellow-Georgian and the head of the N.K.V.D., the security service, followed by Malenkov (Jeffrey Tambor)—next in line to succeed Stalin, and dreadfully pale at the prospect—and Khrushchev (Steve Buscemi), still wearing his pajamas under his suit. Then comes the rest of the gang, including Kaganovich (Dermot Crowley), Mikoyan (Paul Whitehouse), and Bulganin (Paul Chahidi). Notable by his absence is Molotov (Michael Palin), whose wife has been arrested. His own head could be on the block.

The problem, for all concerned, is the idea of a Stalin-free land. If they must jockey for his throne, which of them will be bold enough to start the fight, with their lord and master still breathing? What will happen if, by some miracle, he rallies and learns that certain underlings presumed to step into his unfillable shoes? Meanwhile, he needs the finest professional care, but regrettably most of the doctors in Moscow have been purged at Stalin’s command. (This is the sort of irony in which the movie delights, and it’s far from fanciful; an article inPravda, that year, had indeed denounced “assassins in white coats.”) The only medics still at liberty are dodderers and greenhorns; later, when Stalin’s son Vasily (Rupert Friend), a barely controllable drunk, gets to the dacha and confronts them, he is incensed. “You’re not even a person, you’re a testicle,” he shouts at one, and, at another, “You’re made mostly of hair.”

Vasily is too late, for his father has passed away. Not that death decreases his talent for terror. The hapless doctors are shipped off in a truck, presumably to their doom; they know too much. Stalin’s look-alikes, retained as a safeguard, are now expendable. Mourners, thronging to the capital, are shot on the streets. As for the Central Committee, it seethes with plots and counter-plots. When Stalin’s daughter, Svetlana (Andrea Riseborough), turns up at the dacha, Beria, Khrushchev, and the others run out of the woods, where they’ve been muttering in mini-factions, to press their condolences upon her. In the scrap for lamentation, everyone wants to be top dog.

If that sounds unseemly, just you wait. The dumbfounding thing about “The Death of Stalin” is that it’s a comedy—the broadest and often the bloodiest of farces. It is grossly neglectful of the basic decencies, cavalier toward historical facts, and toxically tasteless. No sooner do the characters stand on ceremony than the movie pushes them off. As Stalin lies in state, his ministerial minions furtively swap positions around the open casket, with one of them exclaiming, “Jesus Christ, it’s the bishops!” To be put in charge of the funeral arrangements, as Khrushchev is, means having to pick out curtains for the catafalque—ruched or non-ruched? You can feel Iannucci working his way through a list of insultables: the holy Church, the pride of the motherland, the need for grief. Not even Marshal Zhukov, the glorious veteran of the Second World War, whose stature remains untarnished today, is spared; Jason Isaacs plays him as a bully with a thick Yorkshire accent. Yet he’s the only man who shows not a shiver of cowardice, and nobody else has the nerve to stand up to Beria. As Zhukov says, “I fooked Germany. I think I can take a flesh lump in a fookin’ waistcoat.”

Let us look at the lump. Not all the actors in Iannucci’s film are at ease with his corrosive tone. Jeffrey Tambor, for example, seems a little uncertain as to how weak and uncertain Malenkov should be, though I liked his bumbling admission “I can’t remember who’s alive and who isn’t.” On the other hand, Simon Russell Beale, as Beria, gathers the story into his clutches and deploys his entire frame; portly though he is, with a creased roll of fat at the back of his neck, there is nothing warm or comforting about Beria’s bulk. He is more beetle than bear, scuttling to and fro with a devilish purpose that Kafka would have noted, and peering at the treasonable world through rimless pince-nez, the better to anatomize its sores and flaws. To inspect is to suspect.

How did Beale, a stalwart of the British theatre who has made a mere pocketful of films, achieve this suppurating portrait of malice? I first saw him onstage in 1990, when he played Thersites—no Shakespearean role is more flecked with spleen—in “Troilus and Cressida,” and latterly, in 2014, as a choleric King Lear, sliding into the cracks of early dementia. In the intervening years, his résumé has included a generous dose of brutes and creeps: Richard III, Iago, and Malvolio, whose parting shot, “I’ll be reveng’d on the whole pack of you,” at the close of “Twelfth Night,” is echoed by Beria, in the new film, as his colleagues finally muster against him—“I have documents on all of you.”

In short, no actor has been more thoroughly trained in the stewing of slyness and bluster that we smell in Beria, who was as baneful a human as has ever breathed. (He was a serial rapist of young girls, but the film, thank heaven, chooses only to glance at that habit; picture someone so morally squalid that his pedophilia counts as a sideline.) When torture is required, he issues instructions with the relish of a gourmet ordering a meal: “Have his wife move into the next cell and start working on her until he talks. Make it noisy.” Or, “Shoot her before him, but make sure he sees it.” What the hell is there to laugh at, you may ask, in this sump of depravity? Should we be surprised that “The Death of Stalin” has been banned in Russia, where one Moscow cinema was raided and fined for screening it? Is it not, as a filmmaker there described it, “a tremendous abomination”?

Well, yes. The damnable problem, however, is that it’s funny; ten times funnier, by my reckoning, than it has any right to be, and more riddled with risk than anything that Iannucci has done before, because it dares to meet outrage with outrage. The hit TV shows that he created—first “The Thick of It,” in Britain, and then “Veep”—bristle with satirical zeal, but you do wonder, after a while, whether the everyday dysfunctions, enraging as they are, of an essentially functioning democracy are not too easy a bull’s-eye for his scorn. It’s hardly news, for instance, that the American Vice-Presidency is kind of a halfway job, and, when the worst that can befall a person is demotion, or an online roasting, how much is honestly at stake?

No such doubts attend “The Death of Stalin,” where every gag is girded with fear. The humor is so black that it might have been pumped out of the ground. To defend the film as accurate would be fruitless; the episode that kicks it off, in which a pianist, having played a Mozart concerto on the radio, is forced to reprise it at once because Stalin desires a recording, occurred in 1944 if it occurred at all, rather than—as here—on the eve of Stalin’s demise. Yet the compression of time is allowable, because the panic and the fawning dread that are instantly triggered by his name, in these opening scenes, ring all too true. Here is a society on the verge of a nervous breakdown.

The question of how many million souls were extinguished either at Stalin’s bidding or as a result of his policies will never be settled. Documentaries can and should engage in that dispute, but no feature film, however sombre and responsible, could begin to dramatize such boundless suffering. Perhaps comedy, far from being disqualified for so unhappy a task, is the only genre that can tackle it. Behind “The Death of Stalin” stretches a long tradition of British grotesquerie, from James Gillray’s scabrous cartoons of Napoleon back to Christopher Marlowe’s two-part “Tamburlaine,” another litany of mass murder. As Beria pursues his sulfurous trade, you don’t know whether to weep, shriek, snigger, or look away, and what goes through your mind is not “This is exactly what happened, in 1953,” but “Yes, here is a man who could do such things. I wish I didn’t believe in him. But I do.” He is a monster for all seasons.

Anthony Lane has been a film critic for The New Yorker since 1993. He is the author of “Nobody’s Perfect.”

No comments:

Post a Comment