His early films lean left, but his Navy service seems to have changed him. He remains an enigma.

By Kyle Smith

January 31, 2018

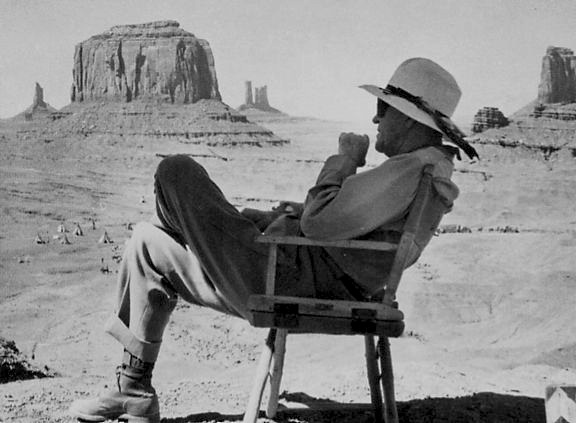

John Ford at John Ford Point, Monument Valley

A piece of John Ford family apocrypha has it that when a relative got off the boat from Ireland, a man asked him whether he’d like to be a bus conductor and wear the fine uniform that went with it. Sure, said the immigrant, and soon found himself in a uniform all right: Union blues, at the Battle of Shiloh. So incensed was he by this turn of events that he defected to the enemy and became a hero fighting for the Confederacy.

The contrarian streak was the essence of John Ford, the only man to win the Academy Award for Best Director four times — no one living has done it more than twice. Perhaps his most acclaimed movie, The Searchers, received no Oscar nominations but now is frequently called one of the greatest films ever made. His collaborator Henry Fonda dubbed Ford “a son of a bitch who happens to be a genius.”

Born February 1, 1894, the cantankerous, self-mythologizing enigma is sometimes derided as a Hollywood reactionary. But he was an avid New Dealer who made the most potent left-wing message movie of all time, cheered on the IRA, and supported the Loyalists in the Spanish Civil War. He pushed back against the blacklist — his FBI file labeled him a “fellow traveler” — but then joined the right-wing Motion Picture Alliance, an ally of the House Un-American Activities Committee. As late as age 70, he told a reporter he was a Democrat, although he had voted for Barry Goldwater. Among Hollywood liberals, he’d call himself a “Maine Republican,” the state of his birth being one that voted for a Democratic presidential candidate only once in the century between the Civil War and the Great Society and where Herbert Hoover beat FDR by a 13-point margin in 1932. In the final years of his life, which ended in 1973, he worked on a hawkish Vietnam documentary even as he privately confided he didn’t see the point of the war.

This month is an excellent one to consider Ford’s legacy: Seven of his features and his Oscar-winning short documentary The Battle of Midway will be airing on TCM in February. (He was a commander in the Navy during that battle; while making the film, he was wounded twice, for which he received the Purple Heart.)

Ford’s pre-war films lean left, especially the melodramatic pro-IRA film The Informer (1935) and the magnificent The Grapes of Wrath, whose vision of a New Deal brand of collectivist action against the forces of capital and cruelty has never been more eloquently realized on screen than in the climactic “I’ll be there” monologue given by Fonda as Tom Joad. Ford won an Oscar for both of those efforts as well as for his last film before the war, the Welsh family drama about a coal-mining community How Green Was My Valley (1941), which makes the case for unionization. Ford accepted many assignments just to stay employed, but in his more considered works, he was nursing a theme of community, of citizens banding together against such oppressive forces as the English and capitalism. Honest citizens are driven to extremes, even to crime, by these dehumanizing external pressures, and at the end of Grapes of Wrath, Tom Joad, who has been forced to kill to survive, essentially leaves his body and becomes one with the American landscape, a secular angel of progressivism sworn to fight injustice.

Ford’s service in the war (he was also under fire for six weeks in North Africa, ran around China with OSS founder Wild Bill Donovan, and went ashore at Normandy a few days after D-Day) seemed to alter his political balance. Shaken by what he’d been through, he decamped to England and went on one of his occasional despairing drinking binges, some of which knocked him out of commission for weeks at a time.

Jimmy Stewart, John Ford and John Wayne

Ford was a longtime fabulist given to describing his life as more exotic than it was; he claimed falsely to have been born in Ireland, that his birth name was Sean Aloysius O’Fearna, to have been a soldier in World War I, and to have served “before the mast.” Even his tombstone repeats a lie; he wasn’t born in 1895. But that’s in keeping with the summa of his deconstructionist 1962 Western The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance — “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.”

In fact, Ford had gone to Hollywood the summer he graduated high school and remained there until the war, but pride in his service record added a crucial new element to his character (he kept many impeccably tailored uniforms on hand and rose to the rank of rear admiral of the Navy Reserve). Now his films reconsidered community through a conservative lens. External forces — notably the opposition in the Indian Wars and World War II — continue to bedevil the protagonists, but the sense of victimization fades, replaced by a stern code of honor, duty, and loyalty. Individuals don’t save the community by dissolving into it but by stepping forward manfully to be counted.

Ford’s pet project for after the war, filmed while he was still on active duty, was They Were Expendable, his fee for which he spent building a recreation camp in Los Angeles for vacationing troops. Though patriotic, it’s shrouded by the sense of doom that dogged the months following Pearl Harbor. The actor Ford discovered when he was a prop boy and USC law student, John Wayne (whom Ford now endlessly razzed for not serving in the war), plays a Naval officer whose P.T. boats are pressed into service as speed bumps to slow down the Japanese while the enemy roars through the Philippines after Pearl Harbor.

Ford moved on to the Wyatt Earp film My Darling Clementine (1946), in which a weary resignation to subdue the lawless forces of the West with civic virtue displaces the genre’s usual freewheeling sense of adventure. Such films, argued conservative professor John Marini of the University of Nevada, Reno, were “an artistic response to the intellectual triumph of progressivism,” setting out to celebrate rather than denigrate the past, in heroic terms of virtue and vice. Ford showed “the fragility of the family and the necessity of the rule of law for its support and defense on behalf of the community.”

Ten years later came Ford’s most unsettling film, The Searchers, an exacting Western adventure whose ambiguity was far ahead of its time: “Be careful deciding what it means,” wrote critic David Thomson of its famous final shot, when Wayne’s Ethan Edwards has taken a journey through racism and savagery to restore order but stands on a threshold because he “is not fit or ready to enter the house again.”

Ethan spends most of The Searchers trying to locate and kill his kidnapped niece Debbie (Natalie Wood) because she “ain’t white anymore,” having been raised by Comanche since she was a small child. By the end, he has regained a moral compass and cradles the rescued girl in his arms. To the extent Ethan embodies, as Garry Wills has written, the “original sin” of our country, his return with Debbie suggests redemption. The Searchers is an uneasy experience, but ultimately it reconfirms an ideal American vision in which indomitable individualists can tame both the frontier and themselves.

The famous closing shot of The Searchers

READ MORE:

50 Shades Freed: 50 Shades of Political Correctness

12 Strong: Moral Clarity about the War on Terror

How to Fix Star Wars

50 Shades Freed: 50 Shades of Political Correctness

12 Strong: Moral Clarity about the War on Terror

How to Fix Star Wars

— Kyle Smith is National Review’s critic-at-large.

No comments:

Post a Comment