We need a designation of the enemy that homes in on its ideology.

There was never going to be justice for the American war dead of the Benghazi attack. The jihadist strike on the eleventh anniversary of the 9/11 atrocities was too bound up in the politics of the 2012 presidential election. Moreover, the prosecution of the lone defendant charged in the attack was a product of the progressive ideological insistence that acts of war can seamlessly be downgraded into mere penal offenses, adjudicated with all the due-process strictures that implies.

This bull-headed conceit is a fiction, and thus the experiment is a failure.

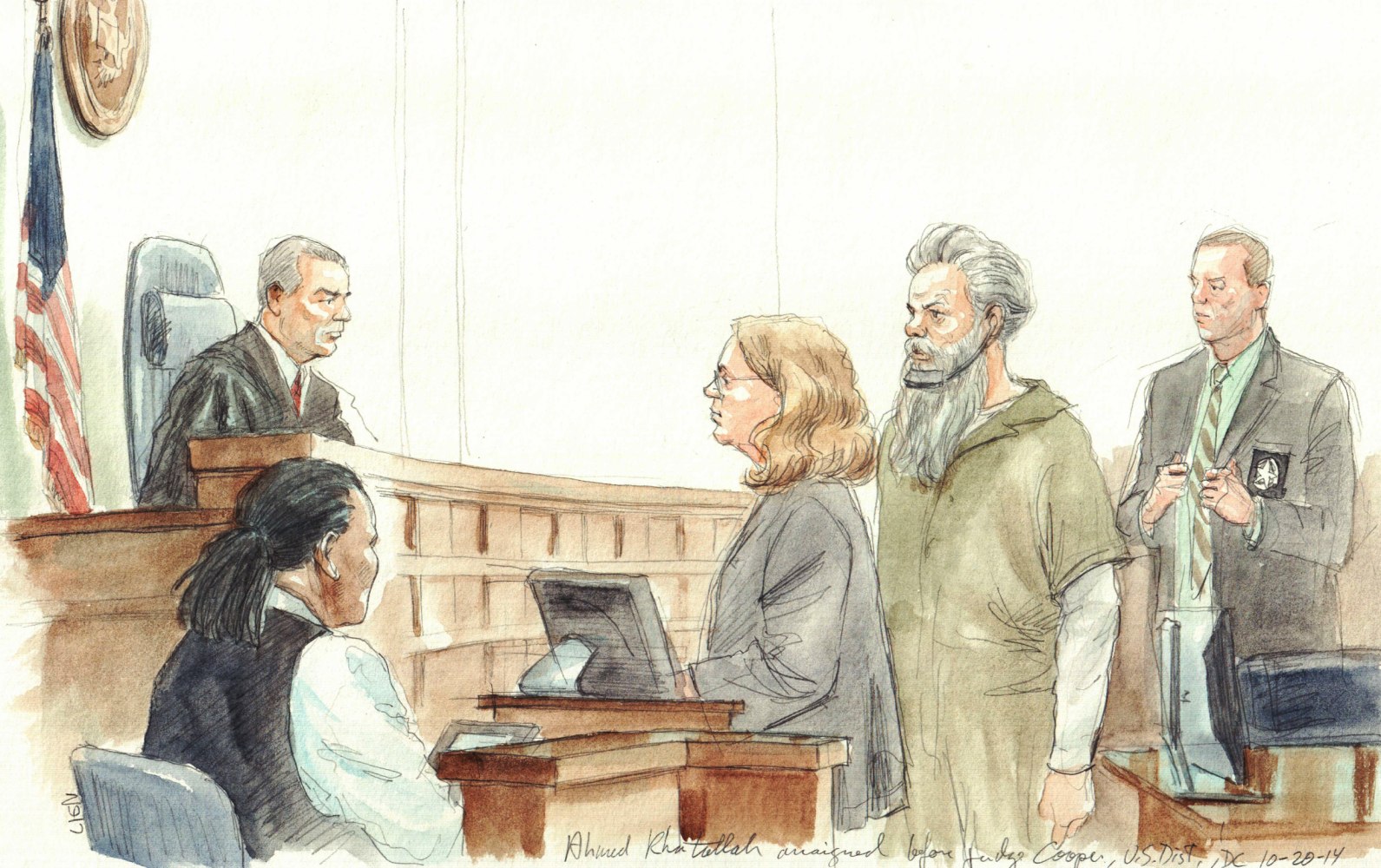

It is not my purpose to make a competing “I told you so” claim that Ahmed Abu Khatallah should have been designated an enemy combatant and consigned to military detention and trial. Yesterday, after an eight-week trial in civilian federal court in Washington, Khatallah was acquitted on the most important charges against him — the charges that arose out of the murders of U.S. ambassador J. Christopher Stephens, State Department employee Sean Smith, and CIA security contractors Glen Doherty and Tyrone Woods. Despite these 14 acquittals, he was convicted on four charges involving material support for terrorism, destruction of property, and carrying a firearm during a violent crime. There is no reason to believe that the outcome would have been more just — or even that we would have an outcome yet — had the case been assigned to the existing, deeply flawed military-commission system.

Instead, in positing two points, I want to restate a plea that we stop playing with fire and move beyond the deadening “military v. civilian” debate — Is it a war or is it a crime? — that has undermined American counterterrorism for 16 years.

Point One: The identification of our wartime enemy must be made with more precision — which is to say, the Authorization for the Use of Military Force (AUMF) under which we have been operating since October 2001 badly needs superseding. It is the AUMF that determines who can properly be regarded as an unlawful enemy combatant. Only unlawful enemy combatants may be detained, interrogated, and prosecuted outside the civilian justice system. It is not clear that the AUMF would have supported Khatallah’s designation as an enemy combatant, notwithstanding his murderous jihadist attack on U.S. government facilities. Part of that is because of the way the Obama administration distorted al-Qaeda, but another part is the increasing obsolescence of the AUMF.

At present, many if not most of the jihadist organizations we confront did not even exist when the AUMF was enacted (although most carry the DNA of al-Qaeda, as that network existed 16 years ago). The problem has long been obvious, even if we remain willfully blind to it: Our enemy is not a particular jihadist network; it is sharia-supremacist ideology, drawn from a fundamentalist interpretation of Islam, which spawns virulently anti-American, anti-Western jihadist factions. The factions come and go, their names changing over time — al-Qaeda, ISIS, Ansar al-Sharia, al-Shabaab, al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb or in the Arabian Peninsula, and on and on. The constant is the ideology. It is what catalyzes the jihadists and knits their ever-evolving forces together.

We need a designation of the enemy that homes in on the ideology and brings within its sweep all these conforming groups. The current AUMF, to the contrary, is circumscribed by a long-ago event (9/11) and the entities (whether terrorist organizations or nations) that were complicit in it.

Point Two: To repeat what I have been arguing for over a dozen years, we need a national-security court. At the moment, we have two models for prosecuting enemy-combatant terrorists: the civilian justice system and the military-commission system. Neither one of them is a good fit. Khatallah’s case underscores the incurable deficiencies of civilian prosecution for acts of war that occur outside U.S. jurisdiction — as did the 2010 trial of Ahmed Ghailani, who was acquitted on 284 of the 285 terrorism counts arising out of his participation in al-Qaeda’s 1988 bombings of American embassies in eastern Africa. Yet, the military justice system is also inadequate to the task of addressing a non-traditional enemy who crisscrosses between the civilian sphere and combat operations.

We are well into a second decade of partisan philosophical argument on this subject. It has gotten us nowhere.

Progressives fantasize that all national-security challenges can be resolved by lawsuits and diplomatic gambits — fallaciously reasoning that, because a conflict may not have a military solution, the solution should not have a military component. They insist that the civilian justice system “works” for terrorism because the comparatively few terrorists who are tried get convicted of at least something — even Ghailani, with his hundreds of acquittals, got a life sentence for the single count of conviction, and a similar fate awaits Khatallah. But apologists for civilian due process ignore that most terrorists cannot even be apprehended, much less tried in our judicial system. Most terrorist planning and attacks occur in dangerous territories where our investigative agencies do not operate and the writ of our courts does not run.

Scores of terrorists were involved in the Benghazi attack. Yet, only two have been captured in the ensuing five years — Khatallah and Mustafa al-Imam, who recently appeared in federal district court in Washington after being captured in Libya. The likelihood of many more arrests is nil. Investigations and captures in these cases rely on foreign intelligence that often cannot be presented in court, and on foreign sources who must be rewarded for their cooperation in ways that would never happen in ordinary U.S. prosecutions. Indeed, a major issue in Khatallah’s trial was an informant easily discredited because our government paid $7 million for his assistance.

In addition, an overseas military battlefield is patently not a domestic law-enforcement crime scene. Case in point, again, the Khatallah trial: Unable to secure the Benghazi compounds from jihadist militias, and angry at the Obama administration for fraudulently claiming that the attack was instigated by an anti-Muslim video, what passes for the Libyan authorities delayed for three weeks the FBI’s access to the relevant sites for an all-too-brief brief forensic examination. This delay fatally compromised the integrity of physical evidence. As my friend Cliff May has quipped, we are not filming an episode of “CSI Kandahar” here. When civilian due-process protocols apply but the exigencies of a war zone taint the FBI’s retrieval and processing of evidence, cases are easily dismantled by competent defense lawyers.

These problems, it should be noted, are separate and apart from the main challenge: It is impossible to try terrorists under civilian due-process protocols without providing them generous discovery from the government’s intelligence files. This means we are telling the enemy what we know about the enemy while the enemy is still plotting to attack Americans and American interests. That’s nuts.

The patent downsides of treating international terrorism as a law-enforcement issue are why critics, myself included, were hopeful that a shift to military prosecution of enemy combatants would improve matters — more protection of intelligence, and due process limited by the laws and customs of war. We were wrong. The experiment has been a dismal failure. To catalogue all the delays, false starts, and misadventures of the military-commission system would take another column or three. Suffice it to say that it was unfair and unrealistic to task our armed forces with designing a legal system on the fly even as they fought a complex war in which, unlike prior American wars, swaths of the American legal profession backed the enemy — volunteering to represent jihadist belligerents in challenges to military detention and prosecution.

Furthermore, even if the military system had performed adequately, it is not clear that Khatallah could lawfully have been prosecuted in it. This goes back to the politics of the 2012 election and the outdated AUMF.

As the incomparable Tom Joscelyn relates, Khatallah was a member of a Libyan jihadist militia, Ubaidah ibn al-Jarrah, that was absorbed into Ansar al-Sharia (AAS) after Qaddafi was overthrown. In Libya, AAS has factions in Derna and Benghazi that have close ties to al-Qaeda. (The head of AAS-Derna, Suffian bin Qumi, was an al-Qaeda operative before being detained for a time at Guantanamo Bay.) The two chapters of AAS, along with three other al-Qaeda tentacles that emerged in the post-9/11 years (al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, and the Mohammad Jamal network), colluded in the Benghazi attack.

This attack and its aftermath, including Khatallah’s capture, occurred in the context of President Obama’s preposterous claim that al-Qaeda had been “decimated.” This political narrative, supported by our politicized intelligence community, held that the killing of Osama bin Laden was the death knell of the terror network. ISIS (“the JV team”) was only just emerging, and the remaining constituents of al-Qaeda were depicted as disorganized neighborhood gangs animated by local disputes. We were to believe that a transcontinental network pursuing global jihadist aspirations was a thing of the past (just like Russia was no longer a geopolitical foe and Iran was no longer seriously interested in “death to America”). To summarize the storyline: The al-Qaeda of 9/11 no longer existed.

That’s rather a problem when the AUMF that describes the enemy we continue to fight is premised on the al-Qaeda of 9/11.

In the airbrushed Obama universe, al-Qaeda was not a factor in the Benghazi attack . . . notwithstanding that, as I’ve recounted, attacks on Americans had been called for by bin Laden’s successor, Ayman al-Zawahiri, who sought to avenge a Libyan al-Qaeda leader killed by American forces. Thus, there was no mention of al-Qaeda in the indictment against Khatallah. Prosecutors limned him as an on-site commander during the attack. But with Obama having sought to erase al-Qaeda from the public mind — rather than to emphasize how al-Qaeda threaded the Libyan factions persisting in the anti-American jihad — it was unclear to the jury exactly what Khatallah was supposedly a commander of.

Again, that’s not to say that military prosecution would have fixed things. If we were going to pretend that the al-Qaeda of 9/11 no longer exists (rather than that it is transformed), what would have been the justification for treating Khatallah as an enemy combatant covered by the al-Qaeda-centric AUMF?

We need to overhaul how we do this.

The jury’s verdict is not rational: Khatallah was convicted of conspiring to provide material support to terrorism that resulted in deaths, yet he was acquitted of causing these deaths — acquitted of murdering American officials in the course of attacks on federal facilities. Nevertheless, the material-support count carries a potential life sentence. It would not be surprising if, as in Ghailani’s case, the judge imposes a life term. And then, naturally, the crowd that regards terrorism as a law-enforcement issue will crow that “the system worked” — despite how close the case came to a disastrous end, despite the scores of jihadists still at large after killing four Americans.

We can forge a hybrid system tailored to the sharia-supremacist threat we face — independent Article III judges overseeing detention, interrogation, and trial of jihadists, as well as intelligence-gathering matters, in a law-of-war framework. Or we can keep doing what we’re doing. The latter should not be an option. Khatallah’s case, like Ghailani’s, should be a wake-up call that we need to leave behind the debate over military-versus-civilian justice. It is long past time to blend what’s best from both systems.

READ MORE:

Hillary’s Benghazi Cover-Up Threatens Terrorism Prosecutions

Why Bureaucracies Don’t Stop Terror

After the Westside Highway Jihadi: What Does ‘Extreme Vetting’ Mean?

Hillary’s Benghazi Cover-Up Threatens Terrorism Prosecutions

Why Bureaucracies Don’t Stop Terror

After the Westside Highway Jihadi: What Does ‘Extreme Vetting’ Mean?

— Andrew C. McCarthy is a senior fellow at the National Review Institute and a contributing editor of National Review.

No comments:

Post a Comment