November 1, 2017

Even in 1979, Bob Dylan could cause a commotion. That was the year he released “Slow Train Coming,” the album that announced his embrace of Christianity, soon to be followed by “Saved” in 1980 and “Shot of Love” in 1981: his born-again trilogy. For those three years, the iconoclast, freethinker and reluctant voice of a generation proclaimed faith in salvation by Jesus Christ (despite his Jewish upbringing), with lyrics that drew a line in the sand. In “Precious Angel” on “Slow Train Coming,” he declared, “Ya either got faith or ya got unbelief, and there ain’t no neutral ground.”

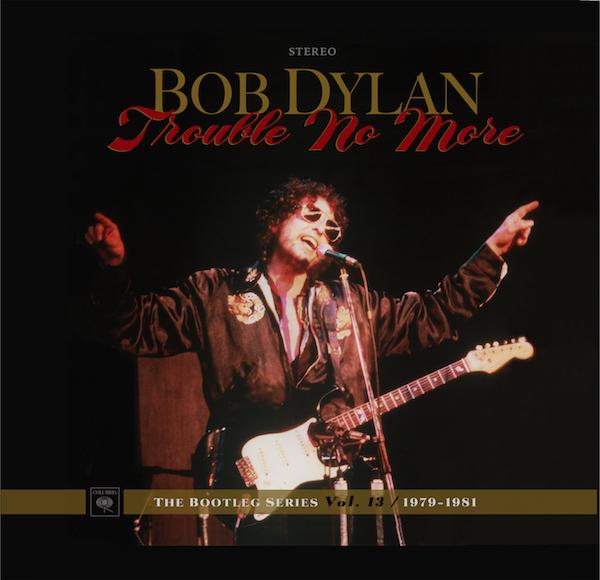

That phase of Mr. Dylan’s music gets a revelatory second look with the boxed set “Trouble No More — The Bootleg Series Vol. 13 / 1979-1981,” to be released Friday. Eight CDs and a DVD collect performances, rehearsals and studio outtakes. The DVD intersperses live footage from 1980 — Mr. Dylan, often camera-shy, clearly wanted this era documented — with fiery sermons written by Luc Sante and delivered by the actor Michael Shannon.

From concerts and recording sessions, the boxed set includes 14 previously unreleased songs to add to the Dylan catalog, notably the remarkable “Making a Liar Out of Me.” A song that first surfaced on the anthology “Biograph” in 1985, “Caribbean Wind,” turns up in a radically different version — gentler, with alternate lyrics — captured at a 1980 rehearsal.

Some fans who had stayed with Mr. Dylan through his multiple transitions since the early 1960s — from folk singer to electric rocker to country crooner to Americana sage — rejected his new, sectarian message. The critic Greil Marcus’s first reaction to “Shot of Love” was that it was arrogant, intolerant and smug.

Doubling down on his message, Mr. Dylan also decided to sing only his new evangelical songs on tour, interspersed with some preaching, though he relented in 1981 and began performing older songs, too. Throughout the born-again years, his audiences would be divided in a way they hadn’t been since Mr. Dylan went electric in the mid-1960s. There were protests outside shows and a mix of enthusiasts and hecklers in the theaters.

Fred Tackett, the lead guitarist in Mr. Dylan’s touring and recording band from 1979-81 (and now a member of Little Feat), recalled in a telephone interview last week seeing a man in the front row holding a sign that read, “Jesus loves your old songs.” The contentious crowds gave Mr. Dylan “a little impetus to go on,” Mr. Tackett said. “I don’t know if he liked it or not, but it inspired him to keep on keeping on.”

Beyond the initial shock of Mr. Dylan’s conversion, many of his Christian songs remain close to the rest of his work. Biblical allusions and echoes of gospel structure were part of his songwriting from the beginning (as in “Blowin’ in the Wind”). So were a sense of moral gravity, a righteous tone, apocalyptic thoughts, and a delight in the rich and powerful receiving their just comeuppance.

Although Mr. Dylan released the three albums within three years, he was evolving fast. “Slow Train Coming” is full of wrathful warnings like “Gotta Serve Somebody” and “When You Gonna Wake Up?” “Saved” moves to direct proselytizing, positive promises and more conventional gospel music. And in 1981, with “Shot of Love,” Mr. Dylan was already looking beyond doctrine, juxtaposing the sacred and secular in rowdy blues-rock like “The Groom’s Still Waiting at the Altar” while praising God in his own way in “Every Grain of Sand.”

Decades later, what comes through these recordings above all is Mr. Dylan’s unmistakable fervor, his sense of mission. The studio albums are subdued, even tentative, compared with what the songs became on the road. Mr. Dylan’s voice is clear, cutting and ever improvisational; working the crowds, he was emphatic, committed, sometimes teasingly combative. And the band tears into the music. The tour recordings provide multiple versions of many songs, yet they’re anything but routine, shifting tempo and attack while Mr. Dylan flings every line with conviction. There were moments of reverence, too, like the quiet coda in the prayerlike “What Can I Do for You?”: just Mr. Dylan on harmonica and the notable soul songwriter Spooner Oldham on organ, sharing experiments in extended harmony.

“He’s always been about change,” Jim Keltner, the band’s drummer, said last week. “What Bob wanted was for people to interact with the music and among themselves. He wanted to hear people playing stuff that he’d never heard before. He wanted people to rise, and we did. I believe that we did.”

With his encyclopedic knowledge of American music, Mr. Dylan cannily chose the backup for his Christian songs: a deep-rooted Southern soul band. He recorded “Slow Train Coming” and “Saved” in Muscle Shoals, Ala., with Jerry Wexler and the keyboardist Barry Beckett as producers; they had worked there on Aretha Franklin’s pivotal 1967 soul hits.

While the studio band for “Slow Train Coming” featured Mark Knopfler and Pick Withers of Dire Straits, Mr. Dylan’s touring band was American and mostly Southern, steeped in gospel, the blues, rock and reggae. Along with Mr. Tackett and Mr. Keltner, it had Mr. Oldham, the bassist Tim Drummond, the pianist Terry Young and a changing lineup of four or five tambourine-shaking female gospel singers. Mr. Dylan originally planned a horn section as well — the set unveils some rehearsal tracks — but the women’s voices were more vivid and jubilant on their own.

They were prolific years. Mr. Dylan discarded more than a dozen songs that show up on “Trouble No More,” among them the Chuck Berry-flavored “Jesus Is the One” and the euphoric affirmation “I Will Love Him.” In “Ain’t Gonna Go to Hell for Anybody,” Mr. Dylan warns of his own guile — “I can mislead people as well as anybody/I’ve got the vision to cause any kind of division” — but insists he has reformed. And in “Making a Liar Out of Me,” over a stolid, inexorable two-chord vamp, Mr. Dylan argues for compassion and conscience: “The hopes and fears and dreams of the discontented/they threaten now to overtake your promised land.”

Mr. Keltner said last week that he cherishes an onstage photograph from the tour by the filmmaker Howard Alk, shot from behind his shoulder. “I’m hunched over the drums, and Bob is standing there with his guitar,” he said. “His hair was this perfectly beautiful Afro, or Jewfro maybe. And the way the light is playing on his hair, it looked like he had a combination of a halo and a crown of thorns. For all the world, it looks like Jesus standing there.”

No comments:

Post a Comment