A Biography That's not The Greatest

September 29, 2017

Important historical figures are like blocks of marble that writers feel compelled to sculpt. More than 15,000 books have been written about Abraham Lincoln. Muhammad Ali won’t reach that mark, but his life invites exploration.

There will always be a need and a market for good Ali scholarship. The most notable of the recent Ali books is “Blood Brothers” by Randy Roberts and Johnny Smith, an extraordinary recounting of the relationship between Ali and Malcolm X that expands what we know about both figures and their time. Other books have succeeded to varying degrees in recounting a particular facet of Ali’s life or his life as a whole.

Some doors close to writers over time. Potential interview subjects pass from the scene. Half of the 200 people I interviewed while researching “Muhammad Ali: His Life and Times” between 1988 and 1990 have died since then. But other avenues of exploration have opened up as government files are declassified and personal archives become available to scholars.

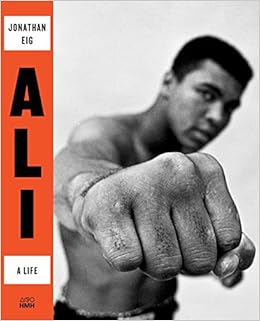

The latest effort at chronicling the life of Muhammad Ali is “Ali: A Life” by Jonathan Eig (published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt).

Referencing Cassius Clay on the night of his first fight against Sonny Liston, Eig writes, “Much of Clay’s life will be spent in the throes of a social revolution, one he will help propel, as black Americans force white Americans to rewrite the terms of citizenship. Clay will win fame as the media grows international in scope, as words and images travel more quickly around the globe, allowing individuals to be seen and heard as never before. People will sing songs and compose poems and make movies and plays about him, telling the story of his life in a strange blend of truth and fiction rather than as a real mirror of the complicated and yearning soul who seemed to hide in plain sight. His appetite for affection will prove insatiable, opening him to relations with countless girls and women, including four wives. He will earn the kind of money once reserved for oil barons and real estate tycoons, and his extraordinary wealth and trusting nature will make him an easy mark for hustlers. He will make his living by cruelly taunting opponents before beating them bloody, yet he will become a lasting worldwide symbol of tolerance, benevolence, and pacifism.”

Thereafter, Eig strips away much of the gravitas that Ali has been clad in over the decades. His work parallels the question asked by journalist Robert Lipsyte: “Do you think that there’s less there than we want to believe was there?”

Eig conducted a massive amount of research. His words are polished and flow nicely.

There are some sloppy mistakes. Eig refers to Maryum, Rasheda, Jamillah, and Ibn Muhammad as “Ali’s children from his first marriage.” But Ali’s first wife was Sonji Roi, and they did not have children together. Belinda Ali (Muhammad’s second wife, who later changed her name to Khalilah Ali) was their mother.

There’s also a lot of hyperbole.

Sonny Liston “pounds the heavy bag so hard the walls shake.” As Clay readies to challenge Liston for the heavyweight championship of the world, “There’s little debate among the men in the press corps about who will win. The question – the only question in most minds – is whether Cassius Clay leaves the ring unconscious or dead.”

Writing about Ali versus Cleveland Williams in The Astrodome, Eig calls the 35,000 spectators in attendance “one of the largest audiences to ever witness a sporting event.” That’s just wrong. Baseball and football drew larger crowds as a matter of course. And where boxing was concerned, Jack Dempsey and Joe Louis drew larger crowds on at least eight occasions.

But there are larger issues to address in evaluating “Ali: A Life.”

Eig is on solid ground in his interpretation of Ali as a public figure and social force. He’s also on point when he writes that, leading into the first Ali-Frazier fight, Ali was “becoming more of a celebrity rebel” than the real thing.

But Eig understates white support for the civil rights movement of the 1960s and sometimes falls into the trap of overgeneralization.

For example, writing of the days after Ali was convicted for refusing induction into the United States Army, Eig states, “White newspaper reporters attacked again.”

So did some black commentators. And there were numerous ”white newspaper reporters” such as Jerry Izenberg, Robert Lipsyte, and Barney Nagler, who vigorously defended Ali.

Also, the platform for Ali’s greatness was boxing. And Eig never captures Ali’s greatness as a fighter, perhaps because he doesn’t understand boxing.

Young Cassius Clay is described by Eig as devastating Allen Hudson at the 1960 Olympic Trials with “a huge right hook.” But Clay was an orthodox fighter. He didn’t throw a “right hook.”

Similarly, Eig writes that, in their 1963 fight at Madison Square Garden, Doug Jones “bashed Clay’s head with a right hook that sent Cassius toppling into the ropes.” Again, it wasn’t a right hook. And Clay didn’t “topple into the ropes.” Then Eig writes, “When the final bell rang, the audience exploded with approval, convinced that their man Jones had won. The TV announcers said they thought the fight might have been a draw. But to the judges and referee, the fight wasn’t close. They awarded Clay the victory by a unanimous decision.”

In that era, fights in New York were scored on a round-by-round basis. Referee Joe LoScalzo inexplicably scored Clay-Jones 8-1-1 for Clay. But judges Frank Forbes and Artie Aidala gave Clay the nod by a 5-4-1 margin. You can’t get much closer than that.

Writing about Ali’s 1966 bout against George Chuvalo, Eig states, “At one point in the opening round, Chuvalo banged fourteen consecutive right hooks to the same spot on Ali’s left side” and adds that, over the course of 15 rounds, “He gave Ali a vicious beating.”

Again, they weren’t “right hooks.” The fighters were in a clinch, Ali had immobilized Chuvalo’s left hand and Chuvalo was pumping his free right hand to the body. More importantly, Chuvalo did not inflict a “vicious beating” on Ali. And Ali won the decision in the Canadian’s home country by a lopsided 74-62, 74-63, 73-65 margin.

Too often, Eig denigrates Ali’s boxing skills. Everyone who follows boxing understands that Ali was diminished as a fighter as his career went on. But there are times when Eig doesn’t give Ali full credit for his ring skills when he was near his peak.

Eig raises the possibility that both Liston fights were fixed. He repeats a claim George Foreman has made intermittently over the years that Foreman’s own manager-trainer, Dick Sadler, drugged George in Zaire. Then, later in the book, Eig recounts a press conference in Chicago when promoter Don King announced Ali’s upcoming fight against Chuck Wepner.

“Why was Dick Sadler, manager to George Foreman, standing by King’s side?” Eig asks. ‘In the months ahead, Sadler and King would work together promoting Ali’s fights, and Sadler would work at Deer Lake as an assistant trainer for Ali. Was this Sadler’s reward for poisoning George Foreman? The answer may never be known.”

This lends more credence to an ugly, unsubstantiated allegation than it deserves.

Eig also travels down a rabbit’s hole with the use of recently-compiled “CompuBox” statistics.

Long before CompuBox turned its attention to Ali, Bill Cayton and Steve Lott ran punch counts on some of Ali’s fights. Two decades ago, Cayton summed up their findings as follows:

“When Muhammad was young, he was virtually untouchable. The two hardest punchers he faced in that period were Sonny Liston and Cleveland Williams. There was no clowning around in those fights. The last thing Ali wanted was to get hit. In the first Liston fight, if you throw out the round when Ali was temporarily blinded, Liston hit him with less than a dozen punches per round; most of them jabs. In the second Liston fight, Liston landed only two punches. When Ali fought Cleveland Williams, Williams hit him a grand total of three times the entire night. But if you look at the end of Ali’s career; in Manila, Joe Frazier landed 440 times and a high percentage of those punches were bombs. In the first Spinks fight, Spinks connected 482 times, mostly with power punches. Larry Holmes scored 320 times against Ali, and 125 of those punches landed in the ninth and tenth rounds when Ali was most vulnerable and Holmes was throwing everything he had.”

Eig devotes a great deal of time and space to statistics compiled recently by CompuBox that show Ali was a different fighter after his exile from boxing than before. But then he goes off the rails, writing that “the percentage of punches landed [by a boxer] compared to the percentage of punches landed by opponents [is] the most telling of all boxing statistics.”

By this measure, summarizing statistics compiled by CompuBox after a review of available fight footage for Ali’s entire ring career, Eig states, “Ali failed to rank among history’s top heavyweights. By these statistical measures, the man who called himself The Greatest was below average for much of his career.”

This use of these statistics brings to mind the old axiom regarding the difference between wisdom and knowledge. Knowledge is knowing that a tomato is a fruit. Wisdom is not putting a tomato in fruit salad.

As more information about Muhammad Ali becomes available, Ali is ripe for reinterpretation. Eig offers readers new details but no new interpretations that expand what we know about, or cause us to rethink, Ali’s importance.

In some ways, the most serious omission here is Eig’s disinclination to discuss the final 20 years of Ali’s life in a more than superficial way. These decades cry out for interpretation. What did Ali mean to the world over the past 20 years? Is there still an Ali message that resonates? In memory, can Ali be a force for positive change? Is there a way to harness the extraordinary outpouring of love that was seen around the world when Ali died.

In 2006, 80 percent of the marketing rights to Ali’s name, likeness and image were sold to CKX for $50 million. These rights were subsequently transferred to Authentic Brands Group. This transaction and its implications (including the “sanitization” of Ali’s image for economic gain) are barely mentioned in Eig’s book.

Lonnie Ali played an enormous role as Muhammad’s wife in overseeing the day-to-day details of living, supervising Ali’s health care, managing his finances and crafting his image over the final 30 years of his life. One can agree or disagree with some of the things Lonnie did. But her presence was at the core of Muhammad’s life; his life was better because she was in it; and her input is largely ignored by Eig.

Nor does Eig acknowledge Laila Ali’s boxing career, the fact that several of Ali’s daughters have married white men or that one of Ali’s grandsons was bar mitzvahed.

Other choices are equally strange.

Howard Bingham was Ali’s best, truest, most loyal friend for more than 50 years. No one was closer to Muhammad than Howard was during the whole of that time. Yet Eig introduces readers to Bingham when he meets Cassius Clay in 1962 and, thereafter, largely ignores him. Other members of Ali’s entourage aren’t mentioned at all. By contrast, while the importance of Bingham in Ali’s life is downplayed, the role of Gene Kilroy (who feuded with Bingham and was one of Eig’s significant sources) is overblown.

But let’s cut to the chase.

Ali, as portrayed by Eig, isn’t a nice man.

Eig’s Ali is not just a womanizer but a vain inveterate whoremonger who was physically abusive to two of his four wives. He’s characterized again and again as having an indiscriminate, selfish, ravenous sexual appetite and verges on being a sexual predator.

Some of Eig’s material is accurate. Some of it is based on rumor and unreliable sources.

I like Khalilah Ali. I think she’s a good woman who was thrust into difficult circumstances and the harshest spotlight imaginable when, at age 17, she married Ali. In February 2016, I conducted a six-hour interview with Khalilah for a documentary that aired on television in the United Kingdom. At that time, I also reviewed an unpublished manuscript that Khalilah had written.

Much of what Khalilah said to me and wrote was compelling and had the ring of truth. Some of what she said was “headline material” but otherwise unsubstantiated and conflicted with what I understood the facts of a particular situation to be.

Eig recounts an incident that supposedly occurred sometime around 1970, when, in his words, “Wilma Rudolph, Ali’s Olympic teammate, [came] to the Ali’s house in New Jersey asking for money to support a child that Rudolph claimed belonged to Ali. Ali admitted the affair with Rudolph, but told Belinda he didn’t believe the child was his.”

It’s a matter of record that 18-year-old Cassius Clay – along with just about every other male athlete on the 1960 United States Olympic team – had a crush on Wilma Rudolph. It’s possible that years later Ali and Rudolph engaged in a sexual relationship. But Wilma was a woman of exceptional dignity and grace. It’s unlikely that she would have appeared at the Ali’s home as described by Eig. The fact that she died of brain cancer in 1994 and is not here to speak for herself makes the allegation ugly.

Looking at the end notes to “Ali: A Life,” one sees that the sole source for the Wilma Rudolph story is Khalilah Ali. One might add that Khalilah gets her comeuppance in the unsubstantiated rumor category when Veronica Porche (Ali’s third wife) suggests to Eig that Khalilah might have tried to poison her.

Eig makes clear his belief that, while Ali was married to Veronica, he was also having sexual relations with Lonnie Williams, who would become his fourth wife.

There’s also an extensive recounting of the children that Ali fathered out of wedlock and references to affairs with girls who allegedly were as young as 12. Some of this has long been a matter of record. Some of it is of questionable veracity. And after a while, it seems like overkill.

Waxing eloquent about Ali’s sexual proclivities, Eig states, “Black women, white women, young women, old women, Hollywood actresses, chambermaids: Ali didn’t discriminate.”

I don’t think that’s accurate. More specifically, I don’t think there were white women.

When Cassius Clay was 13 years old, a 14-year-old African-American named Emmett Till was brutally murdered in Mississippi after allegedly making flirtatious remarks to a white woman. Cassius Clay Sr. talked about the murder incessantly in the weeks that followed, and it made an impression on Cassius Jr on a primal level: Don’t fool around with white women. If you do, bad things will happen.

Later, that message was augmented by black pride.

During my years with Ali, I developed what I considered to be an easy-to-use reliable lie detector test. By that time in Muhammad’s life, he’d become deeply religious. He was doing his best to live his life in accord with what he believed to be the teachings of Islam. Whenever Ali said something I doubted, I’d ask him to “swear to Allah” that it was true. Many a fable (such as the falsehood that young Cassius Clay threw his Olympic gold medal in the Ohio River) was recanted pursuant to the “swear to Allah” standard.

Ali swore to Allah that he never had sexual relations with a white woman.

Further with regard to the issue of white women, Eig writes, “Everyone close to the fighter knew his proclivities.”

Well …

Lloyd Wells was the primary procurer of women in Ali’s training camp (although he had considerable help from others). Wells told me, “Ali was never involved with a white woman. Never, never, never! I’m a guy that tells it like it is, and I don’t think Ali ever had sex with a white woman. He had all sorts of opportunities. They’d throw themselves at him, some big names too. I saw them, but I never saw Ali date a white woman, and I’m sure he never had sex with a white woman. That’s just not the way it was. And I’d know if he had because, on that score, when it came to women, I was closer to him than anyone. I was the one he talked with. I was the one he came to before and after.”

Howard Bingham, as earlier noted, was as close to Ali as anyone on earth. Speaking of Ali and women, Bingham acknowledged, “His habits were bad. When we met in 1962, he looked at girls a lot but didn’t touch. Maybe he’d flirt a little. But even if someone was interested, which a lot of them were, it didn’t go beyond talking. Then Sonji turned him on and, after they split up, there were a lot of women. You know, most men have to wine ʼem and dine ʼem. But all Ali had to do was look at a woman and she’d melt. He got an awful lot of encouragement. But I don’t think there was ever a white woman. Some people have written and some women have bragged that I’m wrong about that. But I know Ali as well as anyone, and I don’t think there ever was a white woman.”

And a final thought …

There was a lot about Jonathan Eig’s work that impressed me as I read his book. Eig conducted an enormous amount of research. He puts words together well. But I never felt comfortable with what I was reading. Then, as I neared the end of the book, I realized what was troubling me most.

Eig fails to communicate how deeply spiritual Ali was in his later years. And he fails to understand what a genuinely nice man Ali was.

In reading “Ali: A Life,” I didn’t see the word “love” attached much to Ali as a human quality. But Ali was a loving man who, in many ways, taught the world to love.

Thomas Hauser can be reached by email at thauser@rcn.com. His next book – “There Will Always Be Boxing” – will be published this fall by the University of Arkansas Press. In 2004, the Boxing Writers Association of America honored Hauser with the Nat Fleischer Award for career excellence in boxing journalism.

An Exhaustive and Engaging Look at the Life of Muhammad Ali

By John Powers

October 6, 2017

Ali fighting Cleveland Williams in 1966

To billions he was known by one name. The only boxer to win the heavyweight crown three times may have been even more famous after he left the ring and became a beloved and inspirational diplomat-at-large.

Muhammad Ali, the most controversial and compelling athlete in history, evolved from arguably the most reviled celebrity in America to the most revered, a magnetic figure who drew crowds across the planet for decades after he retired. “The only difference between me and the Pied Piper is he didn’t have no Cadillac,” Ali once observed.

Jonathan Eig’s exhaustive yet engaging biography, published 16 months after Ali’s death at 74, is the latest of a surprisingly small number of life histories of a rebel who changed his name and transcended his sport. “I had to prove you could be a new kind of black man,” Ali said. “I had to show that to the world.”

While Thomas Hauser’s authorized biography is considered definitive, it was published in 1991. Eig’s account, which includes a detailed examination of Ali’s formative relationship with Nation of Islam leader Elijah Muhammad (and his ill-fated friendship with Malcolm X), also covers the final quarter century of the champion’s life. It includes interviews with more than 200 people including Ali’s three surviving wives plus access to federal government files and voluminous taped conversations between Ali and Sports Illustrated’s Jack Olsen.

Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr. was the great-grandson of a slave, the grandson of a murderer, and the son of a hard-drinking, brawling, womanizing sign painter who beat his wife. His introduction to boxing came with his introduction to Joe Elsby Martin, a white cop in Clay’s hometown of Louisville, Ky. The two met when a distraught 12-year-old Clay reported the theft of his bicycle. Martin trained amateur fighters as a hobby, and he invited the 89-pound Clay, an indifferent student, to come to his gym. “[B]oxing triggered something wholly new in Cassius: ambition,’’ Eig writes.

Clay began his amateur career about a month later, in November 1954, and six years later would win an Olympic gold medal (as a light heavyweight) in Rome, announcing himself with brashness and braggadocio.

His original model was Jack Johnson, the first black heavyweight champion whose victory sparked deadly race riots across the country. “I wanted to be rough, tough, arrogant,” Ali said. “[T]he nigger white folks didn’t like.”

When he fought champion Sonny Liston, a convicted robber and mob enforcer, in Miami in 1964 most of the country was rooting for Liston. “I am the greatest!,” Clay proclaimed after Liston threw in the towel. “I shook up the world.” After Ali (as he was by then was referring to himself) flattened Liston with a “phantom punch’’ in their Maine rematch the following year his primacy was undisputed.

A larger-than-life figure, Ali’s philandering was legendary throughout most of his life. He was married four times and had nine children, two of them out of wedlock. In his extramarital activities “Ali didn’t discriminate’’: “[b]lack women, white women, young women, old women, Hollywood actresses, chambermaids . . . Everyone close to the fighter knew his proclivities.’’

Had it not been for the Vietnam War Ali might well have dominated the decade. But after refusing military induction in 1967, citing his Muslim faith Ali was arrested, charged with draft evasion, stripped of his title, and banned from the ring for more than three years. To many of his countrymen Ali was an ungrateful traitor. To others he was an admirable martyr willing to sacrifice his career and freedom for his religious beliefs.

After four years of appeals the US Supreme Court overturned his conviction but his prolonged absence from the ring took an obvious toll when the 28-year-old Ali returned in 1970. The days when he could “float like a butterly, sting like a bee’’ had passed. To compensate for his flagging legs Ali adopted a risky “rope-a-dope’’ approach, letting rivals bang away at him until they tired.

That strategy helped him regain his crown from George Foreman in the “Rumble in the Jungle’’ in Zaire in 1974 and to vanquish former conqueror Joe Frazier for the second time in the “Thrilla in Manila’’ a year later. But the rope-a-dope also subjected Ali to frightful beatings that likely caused permanent neurological damage. “It was like death,” he said after the third Frazier bout. To many observers it was clear that Ali, who had always lived a lavish lifestyle and supported a hefty entourage, was increasingly fighting largely for the money.

Yet instead of retiring Ali fought for six more years, struggling against rivals whom he once would have befuddled. Ali lost his title to Leon Spinks the following winter and ended his career at 39 with a loss to unheralded Trevor Berbick. “Father Time just got me,” he conceded.

By then the signs of Parkinson’s disease — slurred speech, trembling hands, unsteady feet — were unmistakable. But Ali’s frailty made him a sympathetic character even to his detractors. “They thought I was Superman,” he said. “Now they can go: ‘He’s human like us. He has problems.”

Ali became a beloved icon, a serene and smiling figure who spoke in a whisper. “More and more he is like a soul walking,” wrote sportswriter Frank Deford. For the rest of his life the former champion served as a goodwill ambassador and charitable fund-raiser whose efforts benefited organizations ranging from the United Nations to the Make-a-Wish Foundation.

He traveled widely to Muslim countries and made a pilgrimage to Mecca. Back home, where he had come to be regarded as a global citizen with a unifying message, Ali was chosen to ignite the cauldron at the opening ceremonies of the 1996 Atlanta Olympics. In 2005 he was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by George W. Bush, a fitting turnabout for the man whom Richard Nixon had called “that draft-dodger.’’

After his death from septic shock in June of last year, tens of thousands of mourners turned out for his funeral procession in Louisville. “Muhammad Ali shook up the world,” President Barack Obama observed. “And the world is better for it. We are all better for it.”

No comments:

Post a Comment