Since 2001, C.S. Lewis’s book has sold 3.5 million copies in English alone.

By George M. Marsden

March 24, 2016

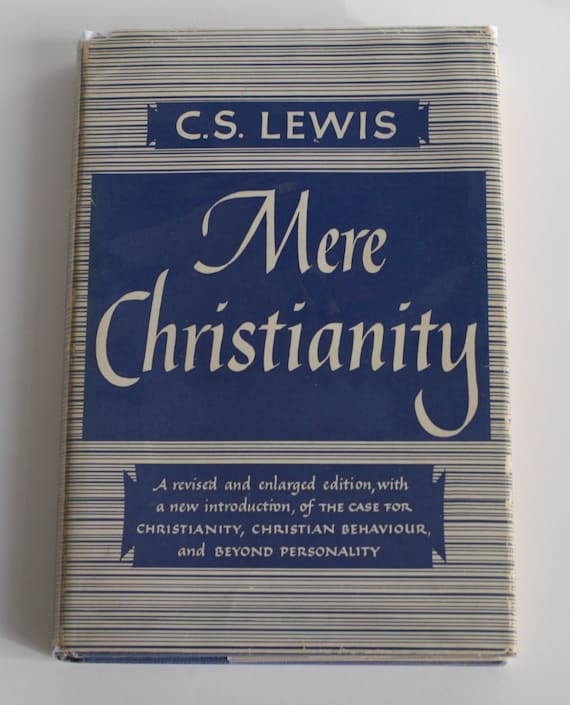

Mere Christianity by C.S. Lewis - First Edition - The Macmillan Company 1952

During March Madness several years ago, the InterVarsity Christian Fellowship’s Emerging Scholars Network ran “The Best Christian Book of All Time Tournament.” Beginning with 64 entries, participants voted on a series of paired competitors through elimination rounds. C.S. Lewis’s “Mere Christianity,” a first seed, easily made the Elite Eight, where it handily defeated St. Augustine’s “City of God.” In the Final Four it beat Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s “Cost of Discipleship,” but in the finals it was edged out by Augustine’s “Confessions.”

Not bad. Who else could have gone up against Augustine? And Lewis hadn’t even planned for “Mere Christianity” to be a book. During the dark days of World War II, the writer presented four sets of BBC radio talks on basic Christianity. He had these published in several paperbacks. Not until 1952 did he collect them together under the new title.

The book always sold well, but in an unusual trend, its popularity has grown with time. Since 2001, “Mere Christianity” has sold more than 3.5 million copies in English. It has been translated into at least 36 languages and is said to be the book that, next to the Bible, educated Chinese Christians are most likely to have read. Its greatest popularity is in the U.S., where it is still read by thoughtful evangelicals, along with thousands of Catholics, Orthodox and mainline Protestants.

What accounts for its lasting popularity? Lewis was determined to present only the timeless truths of Christianity rather than the latest theological or cultural fashions. In the book’s preface, he describes it as an attempt to explain and defend “the belief that has been common to nearly all Christians at all times.”

He elsewhere criticized “chronological snobbery” or the assumption that the popular beliefs of one’s own era were superior to the “antiquated” ideas of the past. The peculiar intellectual fashions of our time, he wisely understood, will soon look quaint to later generations. It is not surprising then that Lewis’s time-proven views are still flourishing while most other mid-20th-century works are nearly neglected.

Lewis’s determination to present only timeless views also helped him avoid political temptation. He believed it divisive to emphasize “Christianity and . . . ” as in “Christianity and the New Order.” In “The Screwtape Letters,” Lewis has the senior devil tell his protégé to encourage a man to intertwine his political and religious beliefs. This eventually leads the “patient” to believe politics is paramount and that Christianity’s value derives chiefly from its support for his party’s positions. Accordingly, Lewis carefully avoided tying his presentation of Christianity to partisan politics.

The writer’s knowledge of history also helped him connect with his audiences. As a prototypical Oxford don, Lewis might have been expected to have difficulty understanding the many varieties of ordinary people who listened to wartime BBC broadcasts. In fact, he used his expertise as a student of the history of literature for the opposite effect.

Studying many eras of literature and language made Lewis acutely alert to the peculiarity of how mid-20th-century British people thought and spoke. He also had a good ear for listening to how ordinary people talked. He saw himself as a translator who worked to bring common Christian teachings into the vernacular.

“Mere Christianity” contains arguments enlivened with images, metaphors and analogies that capture the imagination. The Lewis of “Mere Christianity” is the same as the Lewis of “The Chronicles of Narnia.” Imagination, he believed, was “the organ of meaning,” even if reason was “the organ of truth.”

Lewis’s first ambition had been to be a poet. It shows in his prose, where meaning is often conveyed through vivid analogies. Lewis writes that when God enters your life, he begins “to turn the tin soldier into a live man. The part of you that does not like it is the part that is still tin.” He explains that becoming Christian isn’t an improvement but a transformation, like a horse becoming a Pegasus.

A final strength of Lewis’s book is in his ability to stand aside and point toward his subject—rather than himself. Lewis once wrote that a poet should not be saying “look at me,” but rather “look at that.” Lewis acts like a guide on the journey from unbelief to faith. He points people to see, as he has, the time-tested beauty of God’s love in Jesus Christ. Not everyone will see the beauty or be persuaded. But those who get a true glimpse will be drawn in by its power.

Mr. Marsden, a professor emeritus of history at the University of Notre Dame, is the author of “C. S. Lewis’s Mere Christianity: A Biography” (Princeton University Press, 2016).

No comments:

Post a Comment