'Apocalypto': Driven by A Hunter's Gut Instincts

Stephen Hunter

Washington Post Staff Writer

Friday, December 8, 2006; Page C01

"Apocalypto" turns out to be not a case of Montezuma's revenge but of Mel Gibson's: It's something entirely unexpected, a sinewy, taut poem of action.

Brazenly politically incorrect, it actually connects with another cult film of epic political incorrectness. Old-timers will immediately be put in mind of Cornel Wilde's "Naked Prey" of 1966, a brilliant if racist classic in which the "natives" of an unnamed tribe capture a Briton on safari and, after finding various colorful tortures for his companions, decide to stalk him for sport. The movie then devolves to pure narrative as the valiant, agile, resilient, tough-as-leather-bowstring hunter turns the tables on his pursuers.

The same figure is at the center of "Apocalypto": A hunter being hunted, who turns out to be equally valiant, agile, resilient and tough as leather bowstring. And, like his British antecedent, he hunts back. It isn't pretty, except of course -- by the subversive rules of cinema -- it is, especially when he puts spectacular coups de grace on the most savage of his pursuers. I liked the one where he cracks the guy in the skull with a bone-headed club and this little gurgle of blood, almost dainty, spurts out of the shattered skull. That was cool!

The scene and time demand some explication. It's Mexico's Yucatan Peninsula in vaguely pre-Columbian times, in that seemingly endless epoch when the mighty Mayan city-states ruled supreme and took their pleasures from the land and surrounding peoples with no thought to consequence or brotherhood. They were rulers; everyone else was naked prey.

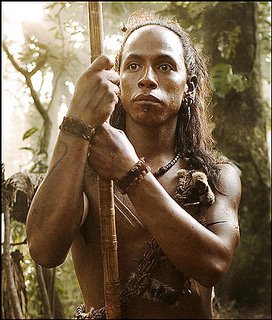

Our hero is no city Maya, however. He is one Jaguar Paw (brilliant, supple, expressive Rudy Youngblood), of an indigenous forest people. Certainly Gibson over-romanticizes this hunter-gatherer lifestyle. In a Potemkin village of surpassing beauty, these happy children of innocence cavort like so many Rima the Bird Girls, chattering in Yucatek (which subtitles translate into a kind of hardy peasant English, bringing to mind Frodo and his mates), joking healthily about sex, living in perfect monogamy in warm little family units under the watchful eye of the benevolent patriarch Flint Sky. Under it, I could see folk memories of Middle Earth or even, for God's sake, Winnetka.

Gibson makes decisions to tell certain forgotten truths. The opening sequence depicts a team bringing down a tapir: The movie gets not merely the necessity of the hunt, and the agony of the beast, but the exhilaration. And when these rangy guys begin the alchemy of butchery by which a corpse becomes meat, Gibson forces you (PETA people, not you ) to feel what they feel: My name will be sung at the tribal fires tonight, my children will go to bed with full bellies, and I will probably get laid.

But this is all about to end. One morning -- the portents have been over-dramatic -- the Mayans arrive in force. And why, you wonder, would the Forest People not even have heard of them and made no preparations, as they are about two days' march from a Mayan urban center? The only answer is that it suits the political agenda of the picture, which is to subvert notions about the "innocence" of native peoples and the "guilt" of usurpers from the outside. In other words, in Gibson's worldview, the Mayans are to the Forest People exactly as, sometime later, the Spaniards would be to the Mayans. It's all a question of empire prerogative.

The results are not pretty. Think of the attack on the village in "Conan the Barbarian" as if really directed by Conan the Barbarian. Gibson's view of the brutal coinage of human exchange, well publicized in "Jesus: The Movie" -- I mean, "The Passion of the Christ" -- is on graphic display, as slaughter is general and bloody, and capture is debasing and grotesque. With the survivors secured by thong and neck brace, the surviving children left to die, the Mayans herd their captives off for disposal.

This begins the film's center passage, a kind of tour of the hell that is the Mayan city-state. We see it from the dazzled captive outsider's point of view. It appears to be late in the day for Mayan rule, as slash-and-burn agriculture has finally used up the land, and so the elaborate trade routes between cities have withered. Plague has struck. The priest-kings of the Maya have turned to human sacrifice for salvation.

The extent of Mesoamerican sacrifice has always been problematic: The latest conclusion seems to be that both the Mayans and the Aztecs practiced it extensively, though the Mayans not nearly as much as the Aztecs, which prompts the question: Why didn't Gibson make a movie about the Aztecs? In any event, his portrayal of the urban lifestyle of the Mayan yuppie class will certainly raise hackles among the self-appointed enlightened, even as it mesmerizes the unwashed. He conjures up a city built around genocide as religious ceremony, and shows the swift deliverance of new victims to the temples, their quick blue paint job (actually more of a cobalt-marine candy coating) and their arrival at the pinnacle of death. There, each in turn is splayed backward over a ceremonial post, his limbs secured by four priests while a fifth performs the myocardial interruption with a flint knife. Talk about the land of the brokenhearted!

The film's version of Mayan culture is -- hmm, what can you say? It's not overly opulent, seemingly made mostly of ziggurats and shanties, with no shopping malls or T.G.I. Fridays anywhere in sight. It reminded me a little of the place where Natalie Portman lived in one of the later "Star Wars" movies, and all the women look a little Princess Padme Amidala. It's just a hair short of out-and-out kitsch and in some venues giggles and snorts will be heard, though the tattoos are very cool and the Nefertiti hairdos all the rage.

You can see where this is going, but that doesn't really prevent you from enjoying it immensely. Jaguar Paw, as it turns out, is the messenger of the gods, he who is specified in prophecy as harbinger of the end of days, according to the movie's official haunted-little-girl truth-speaker. Thus, by various largely unbelievable contrivances, he manages to escape, which sets up the film's last, best hour.

Gibson may not be much of a deep thinker -- and there's no reason why this part of this story couldn't have been set just about anywhere in the world where men kill men -- but he's a heck of a storyteller. The central device of the last hour of the film, Jaguar Paw's freedom run with a crew of Mayan thugs in hot pursuit, is helped by two exceptionally strong, almost demonic acting performances. As the Obersturmbannfuehrer, in a jawbone hat with a fancy knife, is Raoul Trujillo, who exudes aristocratic sang-froid. Then there's Rodolfo Palacios as Snake Ink, more of a weasel than a brute. A terrific actor, he makes you see Snake Ink's guile and wisdom, warped sense of humor and his enjoyment of pain infliction as minor amusement strategy. To Snake Ink, slitting a throat is kind of like buying a new tune for your iPod.

It must be said that whatever its lumpy geopolitical agitprop, Gibson's "Apocalypto" is the lowest, maybe the best kind of -- this is a strange but necessary word for a film this bloody -- fun. It really goes like hell.

Apocalypto (135 minutes, at area theaters) is rated R for extreme violence and gore and disturbing images. In Yucatek with English subtitles.

No comments:

Post a Comment