[One of the best of all time writes about one of the best of all time. - jtf]

[One of the best of all time writes about one of the best of all time. - jtf]The Washington Post

Friday, September 29, 2006; E10

A few hours after learning that he would not be the manager of the Washington Nationals next season, Frank Robinson entered the dugout, the place that has been his home for so much of the last 51 seasons. Every other Nat, driven away by a steady rain, had retreated to the clubhouse.

But Robinson had an appointment to keep two hours before game time. He'd promised to speak with a college journalism class. For Robinson, few days in his life have been harder than yesterday, when he had separate meetings with team president Stan Kasten and General Manager Jim Bowden. "Not as hard as hitting the slider," Robinson said of those meetings, one of which included tears. "Not as hard as managing a baseball team." But, at 71, about as hard as they come.

Yet, at a time when Robinson had every right to sit in his office and argue with the walls, he made time for the George Washington University students. After being introduced to the class as "Dr. Frank Robinson," because of his honorary doctorate from GW, the manager had the whole group laughing at his stories within minutes. For a quarter of an hour in the dugout, he chatted them up, answered their questions, sold his sport, educated a new generation and fulfilled all his responsibilities.

The students left with smiles. Baseball, what a wonderful game, and that dignified Dr. Robinson, how impressive. They didn't know that he had just learned that he would probably never wear a uniform again, never hold a game in the palm of his hand, never be the boss, never feel the pulse of a pennant race and have a whole city cheer for him, as he did just one year ago.

The reason they never guessed the state of his heart is because Robinson has decided to go out with class. Or, more likely, that's just the nature of the man. Whatever conflicted feelings he no doubt has, he expressed no bitterness and harnessed his pride.

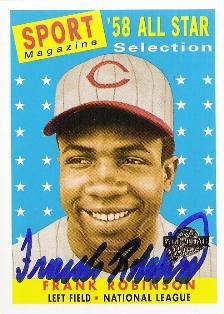

After he finished with the students, he perched on the dugout's back row, watched the rain and talked for half an hour. "I've been fortunate for 51 years," said Robinson, the National League rookie of the year in 1956. "You only get so many chances [to manage]. I felt I'd had my chances. So, I thought, 'Let someone else who's younger have a shot.' Then I got this offer to manage the Expos -- for only one year, I thought.

"And look how it's turned out," Robinson said proudly. On top of his Hall of Fame career and his status as the first black manager, he has now added a dignified and significant Last Act to his eminent résumé. He's been the face of the franchise for a team that returned baseball to Washington after 33 lost seasons. These two brief seasons at RFK now "rank very highly" in Robinson's pantheon of achievements. "Unique and special, very special memories," he said.

However, Frank doesn't want those memories, this new connection with a baseball-hungry city, to end. "If the ballclub would like to have me [next year], I would definitely consider it," he said.

"It would depend on whether the position had real responsibilities. If it does, you got me."

But when he looks at the Nationals current front-office structure, what does he see? "It's pretty full," he said.

"I understand that my role would change as I get older. I may not be as sharp. Some people don't think I grasp that, but I do," Robinson said. "I may want to enjoy life more at some point.

"You have to separate yourself from the game over time. I've been lucky. It hasn't happened abruptly to me -- 51 years," he says, surprised at the number. "That's pretty amazing, especially in this game." He doesn't quite say "cutthroat" game.

"I've always told my players, when your time is over, that's it. The game doesn't owe you anything," he said. "If something is offered, that's a plus."

For Robinson, something of substance absolutely must be offered, no matter how it is carved out. The best quality of the current Nationals -- the cussedness that has allowed them to win 70 games in an injury-devastated season that easily could have produced 100 losses, is almost entirely a reflection of Robinson.

"Frank won't let you quit," catcher Brian Schneider said. "He had a meeting in Colorado [after four straight losses this month] and he talked about how the game has to be played. We came out and started winning.

"Believe me, you don't want to get called into that office."

This week, when an infielder nonchalantly missed a one-hop smash, Robinson called a mound meeting not to chastise the pitcher but to pointedly ask the infielder: "Are you okay? You didn't go after that ball very hard. Are you hurt?" Those words are code: Do it again and I'll jerk you right off the field in the middle of the inning.

"Oh, I've seen him do it," Schneider said.

Robinson chuckles at that recent memory. "If I ask them for the effort, then I've got to give the effort, too, even if it's the last week of the season. All season, the effort has been there. I'm very proud of 'em."

Some players don't respond to Robinson, but those who do are fiercely loyal. "That's very, very sad for him and a lot of us," second baseman Jose Vidro said when he heard the news. "He was here in the hard times and always kept his head up. He thought, with new owners, that he'd have an opportunity to be on the same level with everybody else. . . . I'm a little bit shocked.

That's business."

But now the part of it that includes wearing a uniform is over. The thought of this made Robinson feel "different" and "strange." But he described himself as "at ease," although there was moisture in his eyes when he said it.

"Well, it's time to go," he said at a pregame news conference at which no official announcement was made, but not a shred of doubt was left. Robinson raised his fists like a boxer as he spoke and shadow-punched for a second, as if with his fate. "Just got a bad call from the umpires. They didn't want to reverse it." He meant it, but spun it as a joke.

Asked by the media if he'd been "disrespected" he said, "No, no," emphatically.

In the last half-century there has been no finer baseball man than Frank Robinson. There have been others who deserve a tie with him. His distinction is not that he won MVP of both leagues or managed more than 2,200 games or any of the other standard accomplishments, mountainous though they are in his case.

Robinson's defining distinction was his glowingly upright character, his authentic, often uncompromising integrity. Like his high school basketball teammate and lifelong friend Bill Russell, Robinson always thought out his opinions, whether on baseball or social issues, then spoke them bluntly and defended them consistently.

To describe a baseball manager as "a man of character" would, in many cases, seem ludicrous. Machiavellians and pragmatists, those who hedge their words and cover their backs, often do best in the job. But Robinson chewed out players when he thought it necessary. General managers and owners knew where he stood whether they liked it or not. As Robinson sat and watched the rain in the dugout, he didn't think about himself. He kept talking about the Nats -- the newly acquired speed of Felipe Lopez, Bernie Castro and Nook Logan, the chances of re-signing Alfonso Soriano, the impressive start by rookie Beltran Perez and the unique "makeup" of Ryan Zimmerman. Next year. Robinson only wanted to talk about next year. You can't stop him. His guys are going to be a lot better than people think. Watch and see. If the Nats make Soriano an offer that's "in the ballpark," he thinks the left fielder will be back.

It's clear that, given half a chance to stay near the core of the Nats, Robinson's heart isn't going anywhere.

With a little luck, a little negotiation and common sense, the Nationals and Robinson may actually pull this off. Can the end be graceful?

"Contrary to what some people think, yes, it can," he said.

© 2006 The Washington Post Company

No comments:

Post a Comment