"Government is not reason; it is not eloquent; it is force. Like fire, it is a dangerous servant and a fearful master." - George Washington

Saturday, May 18, 2019

‘It was just perfect’: Southside Johnny on his glory days with Springsteen and Miami Steve in Asbury Park

By Dan DeLuca

https://www.philly.com/entertainment/music/southside-johnny-asbury-jukes-parx-tour-philadelphia-20190509.html

May 9, 2019

When New Jersey’s Asbury Park music scene rose up in the 1970s, there were three bright lights on its rock-and-soul triangle.

Bruce Springsteen was the breakout star. Steve Van Zandt was the songwriter-producer and Springsteen sidekick and consigliere who would go on to The Sopranos and Underground Garage satellite radio notoriety. And Southside Johnny Lyon was the blues and R&B vocalist and bandleader who could outsing both of them.

Starting with I Don’t Want to Go Home in 1976, Southside Johnny & the Asbury Jukes released three classic Van Zandt-produced albums that epitomized the Jersey Shore sound. He’s carried on as a hardworking road warrior for decades since, recording with an ever-evolving Jukes lineup, most recently on the 2015 return to form, Soultime!

Lyon is a key figure in Asbury Park: Riot, Redemption, Rock ‘N Roll, director Tom Jones‘ documentary about the rise, fall, and revival of the central Jersey boardwalk town showing in theaters May 22 and 29.

This week, the 70-year-old singer spoke on the phone from his hometown of Ocean Grove, N.J. He’ll be in Philadelphia with the Jukes at SugarHouse Casino on Saturday

The Jukes were house band at the Stone Pony in the 1970s. But there’s a lot in the Asbury Park movie about the Upstage Club, the after-hours venue that opened in 1968. Why was that place important?

That was our college. It was open from 8 till 5 o’clock in the morning. There was no alcohol, so teenagers could get in. It was two floors above a Thom McAn shoe store.

That’s where I met Bruce and Steve. I already knew Garry Tallent and Vini Lopez. … If they needed a singer — and this was in the guitar-hero era, two verses and then 20 minutes of a guitar solo — I became the singer. So I had to learn all these songs. It was a great education for all of us.

How’d you become a singer?

My parents loved music. Real music … Louis Armstrong and the Hot Fives, the Hot Sevens. T-Bone Walker, Big Joe Turner. This was not the kind of music that other people listened to, but I didn’t know that. I thought this is what people do.

They come home from work, have a couple of beers, and put on [Wynonie Harris’] “Don’t Roll Those Bloodshot Eyes at Me.”

Ocean Grove was a very quiet place. Mostly retired people. Sundays there were no cars allowed on the street. I would hear songs like Louis Armstrong “Struttin’ With Some Barbecue” and it felt like there was life somewhere. We were young and we wanted adventure and there was this music that promised that.

I detested school. My mother worked, and would say it was OK to stay home as long as I cleaned the house. So I would vacuum and make the beds and play their records and sing along with them.

Southside Johnny with Little Steven in Amsterdam (SouthsideJohnny.com)

Shore towns can be cultural wastelands. Why was Asbury different?

The Beatles and the Stones and the Animals — those kind of successful garage bands — it gave us the impetus to try it. To dream a dream of making music. And then there were girls that would look at us, for once.

We never made any money. We were all scuffling. You somehow scrounged your way through and if you weren’t starving to death you got to play on Friday and Saturday night.

Was it a legitimately special place and time?

I think we knew it at the time. I’m not a nostalgist. I don’t look back that much, but when I do I think: How lucky can anybody be?

Bruce, we all thought was really going to be something, though we didn’t expect him to get as huge as he got. But he started to have success after his third album, and we all got the chance to put our foot in the door too. And we were tenacious about it. I wasn’t going back to working at the post office.

So it was a confluence of things. The Upstage Club. The fact that young people were starting to make their own music and there was audience for that. And we were lucky to find each other.

With the African American community on the west side of town, there was a strong black music influence on the scene.

That’s right. I remember going over to the Orchid Lounge and listening to B.B. King play his guitar through the cracked window. And Garry wound up playing with Little Melvin & the Invaders. That was an all-black band that had Clarence Clemons, and there’s this little skinny white kid Garry Tallent playing bass.

There was a place called Piner’s Lounge and Steven and I would go there and Bruce would come and we’d watch Garry play. We weren’t old enough to drink, but because we knew Garry we could get in. We’d eat fried chicken and listen to the band.

You had the great good fortune of Bruce and Steve writing songs like “Hearts of Stone” and “The Fever” and “This Time It’s for Real” for you.

They were’t really written for me. “I Don’t Want to Go Home” might have been. That was really a Drifters thing. I lived with Steven and two other guys, and we would listen to each other’s records. It was such a great time. ... We reinforced our belief in ourselves. We swapped musical educations. We honed our crafts. It was just perfect.

How many people have been in the Jukes?

Right now, it’s over 130.

That’s crazy.

That’s the nature of this kind of long-lived horn band. I had to replace the horn section when they went out with Diana Ross. One of my sax players went with David Bowie. ... I was always of the mind-set of if you get a better offer for more money, take it.

How do you take care of your voice?

I’ve been very lucky. I have a real iron throat. When people ask me for advice, I say, “Get some rest, drink lots of water, don’t party all night, and certainly don’t do cocaine.”

You learned that through experience? Including the cocaine?

Very much so. I wasn’t a big cocaine person, though. I did it once and went on stage and my voice dried out. It’s the stupidest drug. ... I remember a hair band opening for us, and I looked in the dressing room and there was a big mirror with all this cocaine. That’s got to be $1,000 worth of cocaine and you’re only making $500 a night? Economics is not your strong suit.

Who named you Southside?

That’s in dispute. Bruce Springsteen had visited his parents in California. When he came back to N.J., he was broke and needed to put together a band. That was Dr. Zoom & the Sonic Boom. We had a Monopoly game on stage. We had cheerleaders. Baton twirlers. It was crazy. And every musician had to have a nickname. Steve was Miami Steve, and I became Southside Johnny because of my love of Chicago blues.

Not because you were from Ocean Grove, south of Asbury Park?

The great blues mecca of Ocean Grove, New Jersey? No.

AN ODE TO GREAT BOOKS AND A BEAUTIFUL LIBRARY

By W. Winston Elliott III

https://theimaginativeconservative.org/2011/02/ode-to-great-books-and-beautiful.html

February 25, 2011

“If I were rich I would have many books, and I would pamper myself with bindings bright to the eye and soft to the touch, in paper generously opaque, and type such as men designed when printing was very young.

I would dress my gods in leather and gold, and burn candles of worship before them at night, and string their names like beads on a rosary. I would have my library spacious and dark and cool, safe from alien sights and sounds, with slender casements opening on quiet fields, voluptuous chairs inviting communion and reverie, shaded lamps illuminating sanctuaries here and there, and every inch of the walls concealed with the mental heritage of our race. And there at any hour my hand or spirit would welcome my friends, if their souls were hungry and their hands were clean. In the center of the temple of my books I would gather the One Hundred Best of all the educative literature in the world.

I picture to myself a massive redwood table by the artists who carved the wood for King Henry’s chapel at Westminster Abbey (I must be an old reactionary, for I abominate the hard materials that make our concrete homes and iron beds and desks today, and I find something organically responsive to my affection in everything made of wood.) Along the center of the table would stand a glass case protecting and yet revealing my One Hundred Best. I picture my friends treated comfortably there, occasional hours of every week, passing from volume to volume with loving leisureliness.”–Will Durant

I too love great books beautifully bound. Mr. Will Durant may border on idolatry in this excerpt from chapter four of The Greatest Minds and Ideas of All Time, at least my wife suggested the possibility that this may be so. However, she was a gentle critic of this bibliophilic exuberance since she knows her beloved husband would have written this essay himself if he had Mr. Durant’s facility with words. Thank you, Mr. Durant, for this gift to all lovers of great books bound in gorgeous leather, well shelved in a library of dark wood and comfortable leather chairs. Let the contemplation of great ideas and beautiful words never end. Amen.

Books for Imaginative Conservatives are available in The Imaginative Conservative Bookstore. The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

Grievance Proxies

The College Board plans to introduce a new “adversity score” as a backdoor to racial quotas in college admissions.

May 16, 2019

For decades, the College Board defended the SAT, which it writes and administers, against charges that the test gives an unfair advantage to middle-class white students. No longer. Under relentless pressure from the racial-preferences lobby, the Board has now caved to the anti-meritocratic ideology of “diversity.” The Board will calculate for each SAT-taker an “adversity score” that purports to measure a student’s socioeconomic position, according to the Wall Street Journal. Colleges can use this adversity index to boost the admissions ranking of allegedly disadvantaged students who otherwise would score too poorly to be considered for admission.

Advocates of this change claim that it is not about race. That is a fiction. In fact, the SAT adversity score is simply the latest response on the part of mainstream institutions to the seeming intractability of the racial academic-achievement gap. If that gap did not exist, the entire discourse about “diversity” would evaporate overnight. The average white score on the SAT (1,123 out of a possible 1,600) is 177 points higher than the average black score (946), approximately a standard deviation of difference. This gap has persisted for decades. It is not explained by socioeconomic disparities. The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education reported in 1998 that white students from households with incomes of $10,000 or less score better on the SAT than black students from households with incomes of $80,000 to $100,000. In 2015, students with family incomes of $20,000 or less (a category that includes all racial groups) scored higher on average on the math SAT than the average math score of black students from all income levels. The University of California has calculated that race predicts SAT scores better than class.

Those who rail against “white privilege” as a determinant of academic achievement have a nagging problem: Asians. Asian students outscore white students on the SAT by 100 points; they outscore blacks by 277 points. It is not Asian families’ economic capital that vaults them to the top of the academic totem pole; it is their emphasis on scholarly effort and self-discipline. Every year in New York City, Asian elementary school students vastly outperform every other racial and ethnic group on the admissions test for the city’s competitive public high schools, even though a disproportionate number of them come from poor immigrant families.

Colleges pay lip service to socioeconomic diversity, but that concept is inevitably a surrogate for race. Colleges have repeatedly rejected admissions schemes that purport to substitute socioeconomic preferences for racial preferences, on the ground that those socioeconomic schemes do not yield enough “underrepresented minorities.” Harvard admits richer black students with a lower academic ranking over poorer but more qualified white and Asian applicants; it admits more than two times as many middle-class blacks as “disadvantaged” blacks and confers no admissions preference to disadvantaged blacks compared with their non-disadvantaged racial peers.

The SAT’s critics notwithstanding, no alternative measure of student capacity exists that better predicts student success. “Leadership,” “character,” “persistence”—all these earlier attempts to come up with a more politically palatable proxy for racial preferences are far less valid as a measure of academic capacity than the SAT. The College Board’s “adversity score” will be no different. And it will subject its alleged beneficiaries to the same problem as overt racial preferences—academic mismatch. Students admitted to a selective college with significantly weaker academic credentials than the school norm will, on average, struggle to keep up in their classes. Many will switch out of demanding majors like the STEM fields; a significant portion will drop out of college entirely. Had those artificially preferred students enrolled in a college for which they were academically prepared, like their non-preferred peers, they would have a much higher chance of graduating in their chosen field of study. There is no shame or handicap in graduating from a non-elite college. The proponents of racial preferences, like all “woke” advocates, claim to be against privilege. Yet those anti-privilege warriors adopt a blatantly elitist view of college, holding, in essence, that attending a name-brand college is the only route to life success.

The College Board’s adversity score will give students a boost for coming from a high-crime, high-poverty school and neighborhood, according to the Wall Street Journal. Being raised by a single parent will also be a plus factor. Such a scheme penalizes the bourgeois values that make for individual and community success.

The solution to the academic achievement gap lies in cultural change, not in yet another attack on a meritocratic standard. Black parents need to focus as relentlessly as Asian parents on their children’s school attendance and performance. They need to monitor homework completion and grades. Academic achievement must no longer be stigmatized as “acting white.” And a far greater percentage of black children must be raised by both their mother and their father, to ensure the socialization that prevents classrooms from turning into scenes of chaos and violence.

At present, thanks to racial preferences, many black high school students know that they don’t need to put in as much scholarly effort as non-“students of color” to be admitted to highly competitive colleges. The adversity score will only reinforce that knowledge. That is not a reality conducive to life achievement. The only guaranteed beneficiaries of this new scheme are the campus diversity bureaucrats. They have been given another assurance of academically handicapped students who can be leveraged into grievance, more diversity sinecures, and lowered academic standards.

Heather Mac Donald is the Thomas W. Smith Fellow at the Manhattan Institute, a contributing editor of City Journal, and the author of the bestselling books The Diversity Delusion: How Race and Gender Pandering Corrupt the University and Undermine Our Culture and The War on Cops.

Friday, May 17, 2019

Rick Atkinson’s Savage American Revolution

By Joseph J. Ellis

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/11/books/review/rick-atkinson-the-british-are-coming.html

May 11, 2019

THE BRITISH ARE COMING

The War for America, Lexington to Princeton, 1775-1777

By Rick Atkinson

Illustrated. 776 pp. Henry Holt & Company. $40

My old mentor, Edmund Morgan, used to say that everything after 1800 is current events. According to Morgan’s Law, Rick Atkinson has been doing first-rate journalism, enjoying critical and commercial success for three masterly books on World War II, all thoroughly researched and splendidly written. To say that Atkinson can tell a story is like saying Sinatra can sing.

Now Atkinson has decided to move back in time past the Morgan Line, into that distant world where there are no witnesses to interview, no films of battles or photographs of the dead and dying. Visually, all we have are those paintings by John Trumbull, Charles Willson Peale and Gilbert Stuart, all of which are designed to memorialize iconic figures in patriotic scenes, where even dying men seem to be posing for posterity.

Undaunted, Atkinson makes his debut as a historian, determined to paint his own pictures with words. “The British Are Coming” is the first volume in a planned trilogy on the American Revolution that will match his Liberation Trilogy on World War II. It covers all the major battles and skirmishes from the spring of 1775 to the winter of 1776-77. There are 564 pages of text, 135 pages of endnotes, a 42-page bibliography and 24 full-page maps. Lurking behind all the assembled evidence, which Atkinson has somehow managed to read and digest in a remarkably short period of time, is a novelistic imagination that verges on the cinematic. Historians of the American Revolution take note. Atkinson is coming.

He brings with him a Tolstoyan view of war; that is, he presumes war can be understood only by recovering the experience of ordinary men and women caught in the crucible of orchestrated violence beyond their control or comprehension. Here, for example, is Atkinson on Benedict Arnold’s trek with his small army through the Maine wilderness during the ill-fated campaign to capture Quebec, which earned Arnold the title of “American Hannibal” for a feat likened to crossing the Alps with elephants:

“Hemlock and spruce crowded the riverbanks, and autumn colors smeared the hillsides. But soon the land grew poor, with little game to be seen. Ticonic Falls was the first of four cataracts on the Kennebec, and the first of many portages that required lugging bateaux, supplies and muskets for miles over terrain ever more vertical, from sea level they would climb 1,400 feet. ‘This place,’ one officer wrote as they rigged ropes and pulleys, ‘is almost perpendicular.’ Sickness set in — ‘a sad plight with the diarrhea,’ noted Dr. Isaac Senter, the expedition surgeon — followed by the first deaths, from pneumonia, a falling tree, an errant gunshot.”

It is as if Ken Burns somehow gained access to a time machine, traveled back to the Revolutionary era, then captured historical scenes on film as they were happening. At times, Atkinson’s you-are-there style is so visually compelling, so realistic, that skeptical souls in the historical profession might wonder if he has crossed the line that separates nonfiction from fiction. How can he possibly know how the sky looked at Concord Bridge? The sound that ice made as it scraped the boats as Washington crossed the Delaware? Whether Gen. William Howe’s boots were soaked with blood as he walked over the dead and wounded bodies on his way up Breed’s Hill?

The answer is in those almost endless endnotes. Based on my spot-checking of the sources, Atkinson has put his imagination on a very long leash, but it always remains tethered to the evidence. He is not a historical novelist, but rather a strikingly imaginative historian.

Although he is less interested in making an argument than telling a story, the story he tells is designed to rescue the American Revolution from the sentimental stereotypes and bring it to life as an ugly, savage, often barbaric war. Unlike in World War II, most of the killing occurred up close. Advancing troops could literally see the whites of the eyes on the other side, as well as hear horses and men dying in agony. “A man 5 feet, 8 inches tall,” Atkinson observes, “had an exterior surface of 2,550 square inches, of which a thousand were exposed to gunfire when he was facing an enemy frontally at close range.” If he was hit in the torso, his chances of dying were more than 50 percent.

As a result, a larger portion of the population died in the American Revolution than any conflict in American history save the Civil War. Part of the reason was disease; the war coincided with a raging smallpox epidemic. In addition, captured American prisoners had appoximately a 10 percent survival rate; the British were more barbaric in their treatment of prisoners of war than the Japanese in World War II. Instead of a Trumbull, the American Revolution needed a Goya.

Along the way Atkinson provides a steady flow of factual tidbits of the “did you know?” sort. For example, that the recipe for saltpeter, a prime ingredient for gunpowder, was bird dung mixed with urine; that the British Army at full strength required 37 tons of food a day; that one-quarter of the Hessian troops stationed in America decided to remain after the war; that the American obsession with Canada reflected the widespread assumption that it was destined to become the 14th state in the Union; that General Howe’s alleged American mistress, Betsy Loring, was a blond beauty British troops named “Sultana” for her nonchalant demeanor while drinking Howe under the table.

Notice that there is a 15-month gap between the start of the war in April of 1775 and the American declaration of independence in July of 1776. Bunker Hill, the bloodiest battle of the entire war, occurred over a year before a sufficient consensus emerged in the Continental Congress to leave the British Empire. Atkinson pays only passing attention to this political side of the Revolutionary story, devoting more space to the policymakers in London than their counterparts in Philadelphia. His title actually enjoys larger significance than Atkinson lets on, because the decisive factor in converting reluctant patriots to what was called “the Cause” was the looming British invasion in New York. By the summer of 1776 constitutional arguments had become irrelevant. The British Army and their Hessian mercenaries were coming to kill them, destroy their homes and rape their women.

There was also a silent war of considerable significance going on during the interlude between the first shots fired at Lexington and the official commitment to American independence. Atkinson notices it in passing on several occasions, but I hope he will give it the attention it deserves in subsequent volumes. Up and down the Atlantic coast, in every colony, county, town and hamlet, the American resistance movement seized control of the local institutions of governance, requiring oaths of allegiance from all residents, forcing all reluctant revolutionaries to convert and all loyalists to leave. This was not war in the conventional sense of the term, but it was the ultimate reason the British Army was destined to discover that it was on a fool’s errand. As Thomas Paine put it to Adm. Richard Howe: “In all the wars which you have formerly been concerned in, you had only armies to contend with. In this case, you have both an army and a country to combat.”

These caveats are not intended to deter readers, but rather to welcome Atkinson into the fraternity of historians. We are a contentious club of men and women who love to argue with one another. “The British Are Coming” is a major addition to that ongoing argument. A powerful new voice has been added to the dialogue about our origins as a people and a nation. It is difficult to imagine any reader putting this beguiling book down without a smile and a tear.

Joseph J. Ellis’s latest book, “American Dialogue: The Founders and Us,” appeared last fall.

The British Are Coming by Rick Atkinson review — America’s fight for independence

By Gerard DeGroot

https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/the-british-are-coming-the-war-for-america-1775-1777-by-rick-atkinson-review-swg6r9mz5

10 May 2019

On a journey from Kew Palace to Portsmouth in June 1773 George III did not stop at Lotheby Manor in Surrey. According to Rick Atkinson, this was because “an ancient English custom required that if a monarch visited Lotheby, the lord of the manor was ‘to present His Majesty with three whores’”.

One might ask what this has to do with the American Revolutionary War, the subject of this book. To be honest, not much. Atkinson, however, is a lover of detail. The British Are Coming requires 550 densely packed pages to cover only the first two years of the war. The author, a prizewinning American military historian, is never afraid to digress; he interrupts meticulous battle narratives with detours about the treatment of smallpox, or about George Washington’s fondness for Spanish fly, an aphrodisiac made from crushed beetles. This is not a book for anyone in a hurry. Atkinson takes his time, but there’s delight in all that detail.

The American Revolution, Atkinson feels, was no ordinary war. Out of it emerged the American republic — “surely among mankind’s most remarkable achievements”. In other words, the war is a creation story deserving careful narration. It is “a tale of heroes and knaves, of sacrifice and blunder, of redemption and profound suffering. Beyond the battlefield, then and forever, stood a shining city on a hill.”

“The cause of America,” wrote Thomas Paine, “is in great measure the cause of all mankind.” Americans are good at assigning themselves transcendence — that deep belief in exceptionalism remains powerful to this day. Even during this brutal war, ordinary rebels sensed redemption. “Heaven [has]... something very great in store for America,” the artilleryman Samuel Shaw reassured himself after the bitterly disappointing New York campaign. Scribbled in the orderly book of the 2nd New York Regiment were words that read like a hymn: “The rising world shall sing of us a thousand years to come/ And tell our children’s children the wonders we have done.”

Central to every good creation myth is the idea of progress, and better still if that progress is erratic, interrupted by edifying misfortune. In the war’s first skirmish in April 1775 a handful of Americans were massacred at Lexington by British bent on teaching them a lesson. Then a combination of American hope and British hubris shifted the momentum towards the rebels. After the Battle of Bunker Hill in June 1775 and the 333-day siege of Boston, which ended in March 1776, the British were driven from Massachusetts. Americans believed themselves blessed.

General Washington, it seemed, could do no wrong. The might of the British Army and Royal Navy “had been driven off by a rabblement of farmers and shopkeeps”. However, then came humiliation in New York, when the city was captured in 1776, where “Washington and his generals... nearly lost the war... through miscalculation, misfortune, imprudence, and deficient military skills”. The British crowed that victory was near. After that disaster, Washington’s crossing of the Delaware in December 1776 seemed like Moses parting the waters. Fortune shifted again to the rebel side.

American calamity during these years was not confined to the battlefield. “We are in want of almost everything,” Joseph Warren, a leading American Patriot, complained to the Continental Congress in May 1775. Since munitions had to be smuggled past a Royal Navy blockade, there was a perennial shortage of gunpowder and lead. American supplies were often stolen or scavenged from British ships. Lead was collected from fishing weights, clocks, sash cords, downpipes, stained-glass windows and pewter dishes.

Equally worrying was the problem of manpower. These citizen-soldiers would drop arms to return to their fields, factories or shops. Others were taken away by disease. Smallpox was “the pestilence that walketh in darkness”, dysentery “the destruction that wasteth at noonday”. Helpless doctors watched good men waste away. “We had nothing to give them,” one surgeon recalled. “It broke my heart, and I wept till I had not more power to weep.”

Many simply starved. Americans fighting in Canada in the autumn of 1775 were creative in filling their bellies. “Stews were boiled from rawhide thongs, moose-skin breeches, and the rough hides that lined the bateaux floors,” writes Atkinson. “Men gnawed on shaving soap, birch bark and lip balm.” Rifleman George Morison feasted on his leather shot pouch; John Henry ate stew made from a dog and Jeremiah Greenman enjoyed a fine casserole of a squirrel’s head and candlewicks, although he felt it needed salt.

The British also suffered, although their misfortune arose from hubris, that tendency to underestimate their enemy. “They advanced toward us in order to swallow us up,” Private Peter Brown told his mother after Bunker Hill, “but they found a choaky mouthful of us.”

The British learnt quickly how difficult it is to supply an army across a vast ocean. Thirty-six ships left Britain in October and November 1775, but fewer than half reached Boston. Of the 550 Lancashire sheep sent out, only 40 arrived. Hessian mercenaries found themselves without footwear when a large shipment arriving from Portsmouth turned out to be “fine, thin dancing pumps... so small that no use can be made of them”. Troops deserted at a frightening rate, enticed by the American offer of land. Fourteen per cent of Royal Navy sailors absconded during the war.

Americans like their history books big. The reader is often pummelled by a relentless fusillade of facts, which are sometimes mistaken for historical truth. These books are assembled with little regard for eloquence. Not so this one. Atkinson is a superb researcher, but more importantly a sublime writer. On occasion I reread sentences simply to feast on their elegance. Take, for instance: “Plunging fire gashed the column; grazing fire raked it. Men primed, loaded and shot as fast as their fumbling hands allowed... Bullets nickered and pinged, and some hit flesh with the dull thump of a club beating a heavy rug.” In his previous life Atkinson was probably a Romantic poet.

That creation myth, he writes, has “sometimes resembled a garish cartoon, a melodramatic tale of doughty yeomen resisting moronic, brutal lobsterbacks”. That’s certainly the myth I was fed at school in California. The British Are Comingis something entirely different; pages are packed with nuance. Yes, the British raped, brutalised and pillaged, but they were also capable of great valour. The Americans were pretty much the same, but they were fired by that peculiarly American hope. That was sometimes all they had.

The war lasted 3,059 days. It involved more than 1,300 hostile actions and 241 naval engagements. This book covers only the period from the first shots at Lexington in April 1775 to the invigorating American success at Princeton in January 1777. After 18 months of command, Washington had learnt that “war was rarely linear, preferring a path of fits and starts, ups and downs, triumphs and cataclysms”. This book is the first step down that path; we are told that this is volume one of a planned trilogy. Atkinson will be a superb guide through the terrible years of killing ahead.

Thursday, May 16, 2019

Real ‘Mindhunter’ John Douglas recalls most shocking murderer he's met: ‘He put victims in a meat grinder’

By Stephanie Nolasco | Fox News

https://www.foxnews.com/entertainment/real-mindhunter-john-douglas-recalls-the-most-shocking-murderer

May 14, 2019

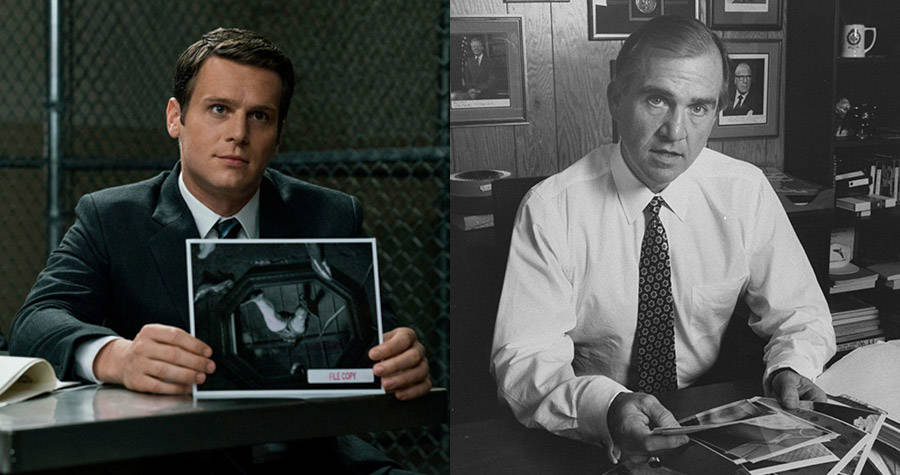

Jonathan Groff as Holden Ford/John Douglas (Netflix/Getty Images)

NEW YORK – Former FBI special agent John Douglas spent his career interviewing some of the most horrific serial killers of all time — but there is one who still haunts him today.

“One was Gary Heidnik out of Philadelphia,” the 73-year-old told Fox News.

"He was even worse than the guy Buffalo Bill in the movie ‘Silence of the Lambs’" said Douglas, whose work profiling serial killers inspired Netflix’s true crime drama “Mindhunter.”

"Heidnik would fill the pit up with water and not drown [his victims] but have them stand in water up to their necks and then get electric wire and torture them while they were in the water. What made it even worse was after he killed them he then would put the victims in a meat grinder and fed the [other] victims… He was definitely shocking."

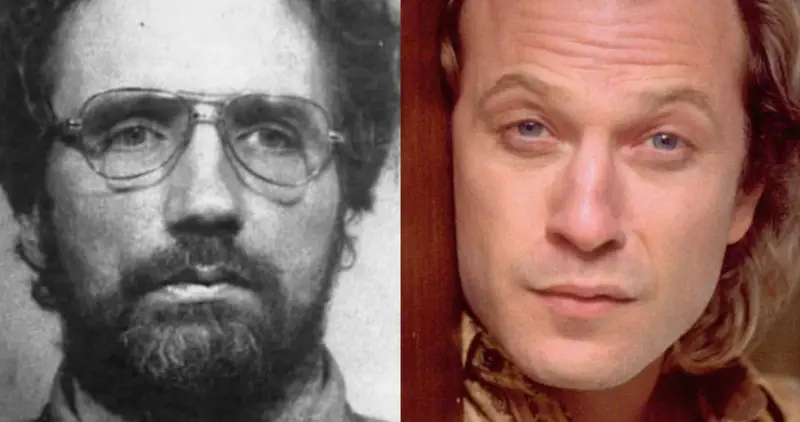

Gary Heidnik and Ted Levine as Jame Gumb in 'The Silence of the Lambs'

The now-retired FBI profiler recently published a book titled “The Killer Across the Table,”which delves deep into the lives and crimes of four disturbing criminals, as well as details the profiling processes he used to crack the cases. Throughout his career, Douglas has confronted notorious murderers, including Ted Bundy, Charles Manson, Edmund Kemper, and “BTK” Dennis Rader, among others.

But Heidnik stuck with him.

"I did that interview with Lesley Stahl for ’60 Minutes.’ It was one of her first interviews. They were about ready to run out of the room during the interview of this guy. He was probably one of the worst ones that I interviewed. There are others but he was pretty bad.”

Heidnik lured six women to his home between November 1986 and March 1987. He kept them half-naked and in chains in the basement of his house. He raped and killed all of them, as well as dismembered two. Heidnik was executed in 1999 at age 55.

Douglas’ work profiling serial killers has inspired Netflix’s true crime drama “Mindhunter,”which is adapted from his 1995 book “Mindhunter: Inside the FBI’s Elite Serial Crime Unit.”The Telegraph reported Douglas was extensively consulted by Thomas Harris when the crime writer was researching “Silence of the Lambs.” The outlet shared Douglas also served as inspiration for the series “Criminal Minds” and also worked as a consultant in the 2009 film “The Lovely Bones.”

One of Douglas’ infamous subjects explored in “The Killer Across the Table” is Donald Harvey, whom he described as the most prolific serial killer to date in American history.

Harvey, known by the press as “The angel of death,” pleaded guilty in 1987 to killing 37 people, mostly while he worked as a nurse’s aide at hospitals in Cincinnati and Kentucky. He later claimed he was responsible for killing 18 others while working at the Veterans Administration Medical Center in Cincinnati. Harvey told his former attorney the killings began in 1970 at Marymount Hospital in Kentucky.

Many of Harvey’s victims were chronically ill patients and he claimed he was trying to end their suffering. Prosecutors said Harvey used arsenic and cyanide to poison most of his victims, often putting it in the hospital food he served them. Some of the victims were suffocated when he let their oxygen tanks run out. Twenty-one of the people Harvey killed were patients at the former Drake Memorial Hospital in Cincinnati, where he worked as a nurse’s assistant.

“What made Harvey so different and where he didn’t become a suspect is… it didn’t have to be predatory,” explained Douglas. “He didn’t have to go out on a hunt. He didn’t have to go on the Internet looking for victims. The victims were in the hospitals. He could go and work at wards, certain wards, where people were very, very sick. Deathly ill. He soon found out that he could kill these people. He made it sound like he was a mercy killer but he was not a mercy killer because some of the things he did were sadistic to the victims, like sticking a coat hanger up through a catheter into a patients abdomen.”

Douglas claimed we don’t truly know how many people Harvey killed because the methods used are difficult to detect.

“It could be in the 90s as they say because the way he was killing them, an autopsy would not detect the way he killed them,” said Douglas.

Donald Harvey

Harvey was ultimately caught after a medical examiner smelled cyanide while performing an autopsy on a victim. After he pleaded guilty to avoid the death penalty, Harvey told a newspaper that he liked the control of determining who lived and died. He died in 2017 at age 64 while serving multiple life sentences after he was beaten by an unnamed person in his prison cell.

Douglas said one of his most memorable interviews was with Charles Manson, whom he once described as a satanic messiah who's “manipulative and charming.”

“What’s amazing about him is how can this 5’2” little guy have the power and control over so many people?” said Douglas. “When you talk to him, it’s almost kind of singsong and like a preacher… He’s a very good reader of body language… During the interview, he said, ‘I got to take something from you. I’ve got to steal something from you.’ [I said], ‘What are you talking about?’ He says, ‘Because everyone knows I’m talking to the FBI right now and I got to give the impression back to them that I took something belonging to you.’

“[I go], ‘Like what?’” continued Douglas. “He goes, ‘Those nice sunglasses you have right over there.’ I said, ‘These are expensive.’ He goes, ‘I’ve got to have it.’ I give him the sunglasses so he has [them] to go back into his cell and say, ‘… Look at what I took. They didn’t even know I ripped them off. I took these glasses from them.’”

The hippie cult leader who masterminded the gruesome murders of pregnant actressSharon Tate and six others in Los Angeles during the summer of 1969 died of natural causes in 2017 after nearly a half-century in prison.

Douglas also recalled speaking with Jerry Brudos, who preyed on young women in Oregon during the late ‘60s. Brudos, known as “The Lust Killer” and “The Shoe Fetish Slayer,” was one of several criminal personalities featured in Season One of “Mindhunter.”

“He said, ‘John, I have hypoglycemia,’” recalled Douglas. “‘When I have an attack I can just walk off to this building and kill myself accidentally because I’m just out of my mind.’ What he’s doing is giving me what you call excuse abuse. That the reason he killed all these women and cut off their foot and took pictures of them wearing high heel shoes is because of this hypoglycemia attack that he would have… If you hear something like that you kind of chuckle and then you’ll say, ‘Wait a minute. I know the case you’re talking about. You didn’t do that.’”

The New York Daily News reported Brudos’ original plea was not guilty by reason of insanity. However, psychiatrists determined that although he was extremely twisted, Brudos’ crimes were not only well-planned but he was aware of his actions. He then changed his plea to guilty, got life in prison and died of cancer in 2006.

Douglas said he hopes his new book will compel readers to become more cautious of their surroundings, especially those attempting to find romance online — a place where predators could be “fishing” for their next victim.

“You have to be suspicious of people,” he explained. “You don’t want to make everyone paranoid… but with these dating sites that women go on, you better be a profiler yourself. You better be able to ask questions about the person. They could be lying but you’ve got to ask enough questions… Don’t randomly go with someone who looks nice, looks decent. You can’t go by looks.”

The Associated Press contributed to this report.