By

December 14, 2018

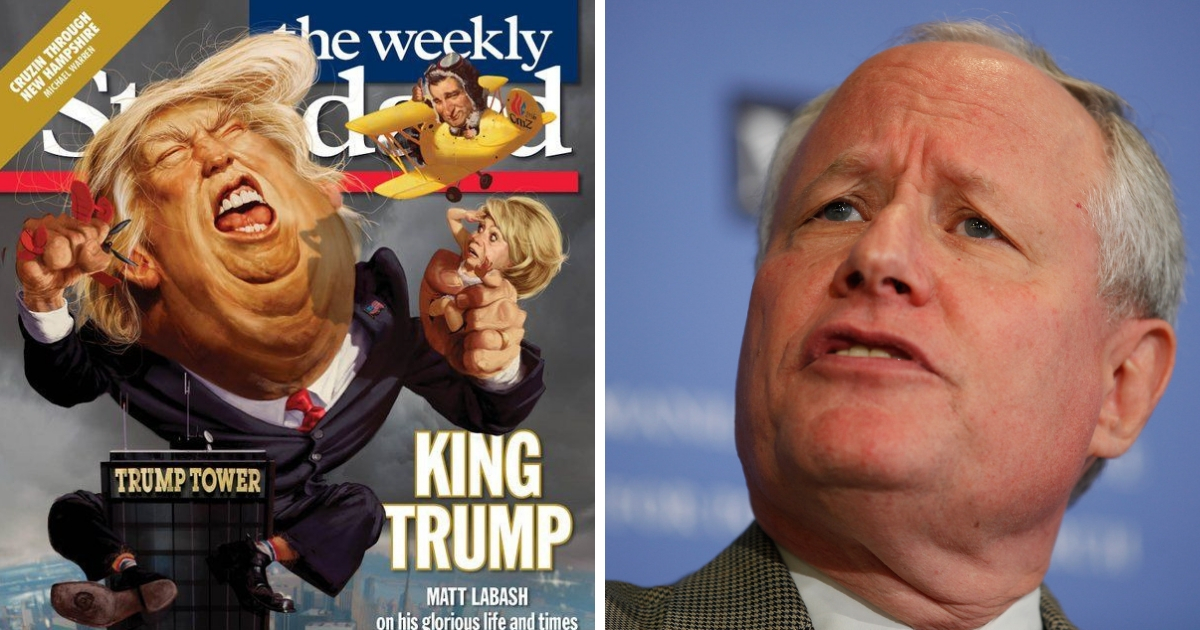

Bill Kristol

The Weekly Standard is no more. Its parent company is shutting the magazine down after 23 years. It is hard to imagine that the magazine that was the home to such greats such as Andrew Ferguson, Matt Labash, and Christopher Caldwell no longer exists. Those are the times in which we live. That’s quite a “Merry Christmas” from owner Philip Anschutz, a conservative Evangelical worth over $10 billion.

Last week, when word got out that this was probably about to happen, my old boss Daniel McCarthy, who was TAC’s editor for years, published a thoughtful analysis of the magazine’s demise. You may not know that the Standard began as a Rupert Murdoch product, and was sold after a while to the Colorado billionaire Anschutz. This business model is different from the one behind National Review and TAC, as McCarthy explains. Excerpts:

The Weekly Standard’s value lay in the fact that it was an insider magazine. It was a top-down product — there was never an independent mass audience clamoring for a second National Review or for a specifically neoconservative publication. (Commentary, as a monthly, already served that market as far as demand could justify.) What was important was that the magazine be read not by a mass market but by Republican officials and their staff and various other influential persons, primarily in Washington, D.C. If officialdom read the Weekly Standard, then it was worth continuing to spend millions on it. In business terms as well as ideologically and literarily, the Weekly Standard had a lot in common with the New Republic, which for decades was dependent upon Marty Peretz’s singular financial support as owner of a magazine that touted itself during the Clinton years as the ‘inflight magazine of Air Force One.’

In Trump’s Washington, a conservative magazine that is robustly anti-Trump loses its practical value. Along these lines:

Beyond that, however, think about the brand itself: in the public mind, the name Weekly Standard is associated with one thing that’s unpopular with almost everyone (the Iraq War), and another that’s unpopular with its formerly intended audience of conservatives (opposition to Trump). The person most identified with the brand is Kristol, by far. He stepped down as editor at the end of 2016, but his public persona still defines the magazine: his bitter, flippant, or sarcastic tweets about Trump and Trump supporters are the Weekly Standard’s brand in the public’s eye. Few people look at the masthead of a magazine closely enough to realize when a prominent editor such as Kristol has been replaced by a less prominent once such as Steve Hayes — and because Kristol remains on the masthead as editor-at-large, ordinary readers have even more cause for confusion. (‘Editor-at-large’ sounds a lot like ‘editor’ to most people, but in fact usually means ‘ex-editor.’)Fairly or not, Bill Kristol is the brand.

That’s simply the truth — and when Kristol did ugly, indefensible things, like accusing Tucker Carlson of defending slavery, it reflected on the magazine, even though he was no longer its editor. National Review even published a cover story denouncing Trump during the 2016 GOP primaries, but it has continued to thrive, in part because of its business model, and in part because it doesn’t have the branding challenge that the Standard has, or had.

I’ve read online some paleocon gloating over the Standard‘s end. You won’t find me doing that. Though I no longer share the magazine’s politics — the Bush years, especially the Iraq War, broke me of that — I retain affection for the Standard and its writers. Being away from the East Coast for so long has given me a spirit of genial ecumenism with regard to other conservative publications, even if I don’t agree with them on all things.

Besides, it is almost never a good thing for a little opinion magazine to go away. If you work for a magazine like this, whether on the left or the right, you know well how difficult it is to make the damn thing happen at all. I don’t know how they did it at the Standard, but every time I visit TAC’s headquarters in DC, I always think that I wish our donors could see how it works at the Mothership. It is a very lean operation; their money really does go into the production of the magazine. I remember making my first visit to National Review‘s New York office back in 2001. I expected to see the decorative equivalent of Bill Buckley (oak-panelled chambers, the faint aroma of dusty books and sherry, etc.). What a shock to discover that the place, bathed in fluorescent lighting, looked like a public interest law firm!

The point is, magazines like ours are a lot cheaper to run than you’d think, given the splash their writers and editors can make. (When I was living and working in NYC, I would show up on cable TV a fair bit, which caused a lot of folks to think I was getting rich — oh, if only!) Some years back, I was present in a conversation in which Bill Kristol talked about what it was like going to the annual retreat of senior editors of Murdoch media properties. The Standard was an asterisk on the annual News Corp balance sheet, but because it mattered in Republican Washington, Kristol and the team he represented punched far, far above their weight.

As John Podhoretz, one of the magazine’s founders, points out in his angry obituary for the Standard:

To be sure, it has never made money. Magazines like it never make money. But its circulation has always been extraordinarily healthy in opinion-journal terms. And within the giant corporations run by the wealthy men who started the Standard and then bought it—Rupert Murdoch and then Anschutz—its annual losses were a rounding error, akin to the budget for the catering on one of their blockbuster movie productions. But if Anschutz had been motivated by an unwillingness to bear the cost any longer, he could have sold the Standard. He chose not to. He chose to kill it.

As McCarthy points out, killing the magazine was arguably necessary to boost the prospects of the Washington Examiner, which Anschutz is expanding to a national audience. Nevertheless, you’d have to have a heart of stone not to grieve the losses of “business decisions.” Then again, I’m the kind of guy who, if I became a billionaire, would be happy to lose money on publishing a magazine that was home to good writers. That’s probably why I’ll never be a billionaire, actually.

In 1995, when Podhoretz, Kristol, and Fred Barnes were staffing up the new magazine prior to launch, they called me over at The Washington Times and asked me to come in for a job interview. I was incredibly nervous about it. I had only been in Washington for a handful of years, and every single day had to fight off my personal demons telling me that I was a fraud who ought to just get back to the bayou and never presume to think that I had a place in national journalism.

I went over to the magazine’s offices, met Podhoretz and Barnes, and sat with them for about 45 minutes. I have no memory at all of the meeting. I just wanted to get out of there without wetting my pants, such was my anxiety. I didn’t get a job offer, and ended up moving to south Florida to get back into arts journalism. Three years later, Podhoretz, who was at that time a top editor at the New York Post, asked me to apply for a film critic’s slot at that newspaper. I did, and got the job; Pod became a good friend — and more than a friend; my career has been enabled by a number of generous people along the way, but none have been more important than John Podhoretz, to whom I owe a debt I can never repay. To be honest, I mostly feel bad today about the Standard‘s fate because I know how much he’s hurting, and I don’t want my friend to hurt.

Anyway, Pod asked me around that time if I remembered my job interview at the Standard. Lord no, I said; I was so nervous that I just wanted to be done with it. He told me that I spent 45 minutes explaining to him and Fred Barnes why I ought not be hired, because I was not good enough to work there.

I had to laugh. Of course I did! In those days, my insecurity more than once led me to self-sabotage. Happily for me, I grew up.

Today, in light of this sad news from Washington, I count it as one of the highlights of my professional life that I was once thought to be a good enough writer to work for the Weekly Standard.