https://www.nationalreview.com/

April 4, 2018

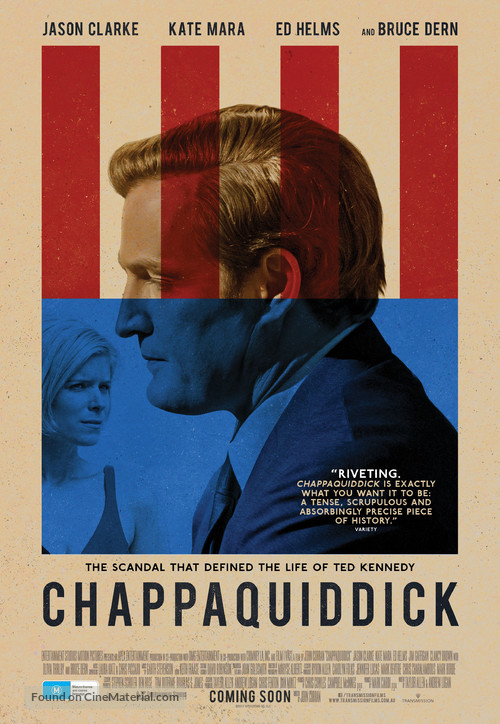

Chappaquiddick must be counted one of the great untold stories in American political history: The average citizen may be vaguely aware of what happened but probably has little notion of just how contemptible was the behavior of Senator Ted Kennedy. Mainstream book publishers and Hollywood have mostly steered clear of the subject for 48 years.

Chappaquiddick the movie fills in an important gap, and if it had been released in 1970, it would have ended Kennedy’s political career. (It was only a few weeks ago that a sitting senator resigned over far less disturbing behavior than Kennedy’s.) Yet this potent and penetrating film is not merely an attack piece. It’s more than fair to Kennedy in its hesitance to depict him as drunk on the night in question, and it also pictures him repeatedly diving into the pond on Chappaquiddick Island, trying to rescue his brother Bobby’s former aide Mary Jo Kopechne (Kate Mara). He may or may not have made such rescue attempts. Moreover, as directed by John Curran (The Painted Veil), the film is suffused with lament that a man in Kennedy’s position could have been so much more than he was. Yet Ted, the last and least of four brothers, was shoved into a role for which he simply lacked the character. That the other three were dynamic leaders who died violently while he alone lived on to become the Senate’s Jabba the Hutt is perhaps the most dizzying chapter of the century-long Kennedy epic.

Jason Clarke, an Australian, is superb as Ted, who as of July 18, 1969, is mulling a run for president in 1972. To that end, he gives a solemn TV interview and then, when the cameras are off, turns to his family flunkies and insists that they round up the juicy “boiler-room girls” without whom, he says, there can be no Friday-night party at the beach cottage, on the island at the eastern edge of Martha’s Vineyard. Kennedy’s wife, Joan, being pregnant, is home on bed rest. Meanwhile, the space program that John F. Kennedy championed is two days away from culmination in the moon landing. The contrast between one’s brother’s far-reaching vision and his soft-bellied sibling’s grubby venality is so conspicuous that you could castigate the screenwriters for inventing it; except they didn’t.

Kennedy drove his car off the bridge, probably recklessly and probably — given that he was coming from a party after 11 p.m. and was a lifelong boozer — under the influence of alcohol. He slipped out of the car, but while Kopechne was trapped inside, he didn’t call the police. Instead he rested by the water for 15 minutes. Then he went back to the party to fetch his cousin Joe (Ed Helms) and their friend Paul Markham (Jim Gaffigan), a former U.S. attorney for Massachusetts, to seek their advice. They tried to rescue Kopechne but couldn’t either and told Kennedy to call the police. Instead, he went back to the inn where he was staying and went to sleep. By the time he sauntered into the town hall to tell the police the next morning, nine hours after his drive, they had already discovered the body.

Some speculation is unavoidable in the screenplay, but what is known is damning, indeed infuriating, and seeing these events play out on screen lends them the capacity to shock us all over again. The combination of arrogance, incompetence, and casual corruption on display is straight out of Veep, but this time it happens while the corpse of a 28-year-old woman is being zipped into a body bag.

Kennedy is having a casual breakfast when his friends arrive at the hotel in a panic. While they try to explain how dire things look for him, he lounges on a bed in his room. At the police department, the chief isn’t present, so he strolls in, sits in the chief’s chair, closes the blinds, and starts strategizing. The chief, when he returns, accepts the senator’s written statement and asks whether there’s anything else he can do for poor Ted. Days later Kennedy will wear a neck brace at Kopechne’s funeral, affecting an injury, which doesn’t stop him from craning around to see who else is present. He plants a story in the media that he has a concussion and is on sedatives, only to learn that no doctor would prescribe sedatives for concussion. Calling Kopechne’s mother to inform her of the news, Kennedy neglects to mention he was driving the car in which she died.

Only the patriarch himself, Joe Kennedy (Bruce Dern), who is undone by a stroke and has only four months to live, reacts with the proper fury, slapping Ted on behalf of the nation. Imagine having sons like Joe Jr., John, and Robert and being left with only this one, the one expelled from Harvard for cheating, the one who was cited for reckless driving while a law student. Ted himself recognizes the futility of trying to match his legendary brothers: After what they did, he asks, what sobriquet does that leave for me? The fat one? The dumb one? An early scene of Kennedy racing his sailboat nails his personality: sloppy, vain, entitled, a man you wouldn’t trust to change your tire.

Yet in the end, aided by a confluence of forces both extraterrestrial (Apollo 11, which dominated the news that week) and tribal (Ted Sorensen, the family expert in blowing smoke), Senator Kennedy managed to save his career. All that Massachusetts voters required was a sincere apology, and he could fake that.